Mercedes Azpilicueta: overlooked knowledge and new perspectives

At Art Rotterdam, taking place from 28 to 30 March 2025 at Rotterdam Ahoy, Prats Nogueras Blanchard from Madrid and Barcelona will present the work of Mercedes Azpilicueta. Her work will be shown in the New Art Section, curated by Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu. Azpilicueta is fascinated by unheard voices and explores how art can contribute to rewriting history from a decolonial and feminist perspective. For Azpilicueta, history is anything but singular: she interweaves the stories of feminist icons, queer individuals, exiles and migrants — figures often overlooked in mainstream historiography — into complex and multidimensional installations. In doing so, she examines the subjectivity of language, history, narratives and objects, questioning their established meanings.

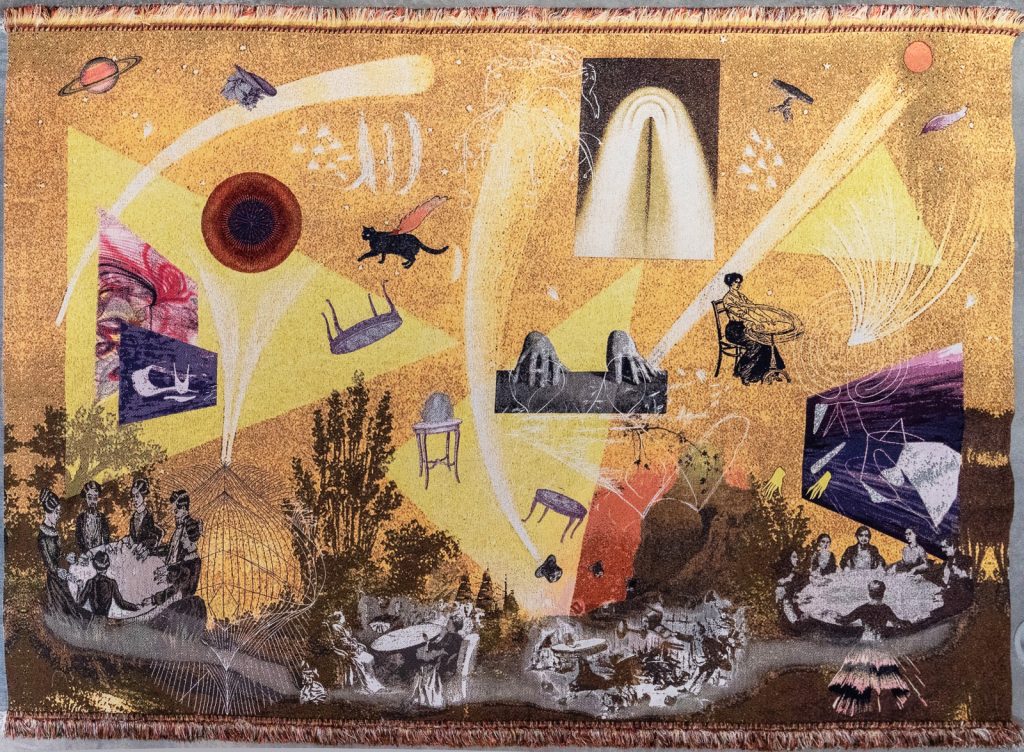

Azpilicueta's multidisciplinary practice spans textiles, sculpture, video, sound, drawings and performance. Textiles hold a central place in Azpilicueta’s practice, where she seamlessly blends traditional techniques like embroidery and weaving with contemporary production methods. That way, she revalues traditional forms of female labour and overlooked knowledge while investigating the impact of power structures on personal narratives. Her Jacquard tapestries feature layered compositions of historical and contemporary imagery, text fragments and abstract forms. At times, she presents these tapestries as sculptures, blurring the boundaries between artistic disciplines.

Her approach is deeply rooted in research. Azpilicueta describes herself as a "dishonest researcher," freely navigating between art history, popular culture, mythology, literature, protest cultures, street culture and personal memories. Azpilicueta also draws inspiration from speculative and fictional Latin American literature, in which alternative realities, future visions and magical realism play a key role. Baroque art, brought to Latin America through colonisation and merged with local traditions, also plays an essential role in her practice. Additionally, the artist is drawn to older forms of knowledge that has been primarily passed down through women, but has often been marginalised by the rise of religion, capitalism and modern medicine. Rather than pursuing a linear reconstruction, Azpilicueta engages in a process of recomposition, where historical facts, fiction, and personal memories seamlessly blend together. In this way, she brings together a wealth of voices, time periods and materials.

Recurring themes in her work include decolonialism, feminism and gender, diaspora and displacement, and the tension between the personal and the collective body. Her associative practice dismantles entrenched historical narratives, creating space for new perspectives. These perspectives are affective, emphasising emotion, bodily experiences and sensory perception as ways to understand and interpret the world. Azpilicueta acknowledges that human experiences are shaped not only by rational or intellectual processes but also by feelings such as empathy, longing, pain and connection. At the same time, her work offers a dissident perspective that challenges dominant views, structures and power dynamics. This form of resistance finds its roots in feminist, decolonial and queer theories, striving to carve out space for alternative narratives, identities and forms of knowledge that fall outside the established discourse. In her work, these two perspectives converge and Azpilicueta offers us alternative ways of understanding and experiencing history. Reflecting on her exhibition at the Fries Museum, the artist stated: “[I] approach history as something multiple, collective, and fluid — something that is never definite but is constantly being rewritten, retold, shared and even contested.

This approach is beautifully reflected in the tapestry “The Captive: Here's a Heart for Every Fate”, that is part of the Van Abbemuseum collection. Inspired by the 19th-century retelling of the legend of Lucía Miranda by Argentine writer Eduarda Mansilla, the piece challenges the original colonial narrative. In the traditional myth, Lucía is portrayed as a passive ‘cautiva,’ a European woman captured by the local Argentine population in the 16th century and ultimately ‘rescued’ by the colonisers. Mansilla subverts this narrative by giving Lucía an active role, while allowing space for her feelings and desires. She highlights the solidarity Lucía builds with the women she lives with, exchanging knowledge and developing their own language. This perspective humanises the Argentine population, showcasing their strength and pursuit of independence without reducing Lucía to a victim. For this work, Azpilicueta drew inspiration from the intricate patterns of 19th-century costumes and corsets. Additionally, the work references a painting by Argentine artist Ángel Della Valle from the same period, but she deliberately reverses gender roles in some cases. Azpilicueta also reinterprets a painting by Uruguayan artist Juan Manuel Blanes, where the allegorical contrast between the ‘barbaric’ and the ‘civilised’ is visually explored. Azpilicueta raises critical questions about these constructed dichotomies and the colonial ideologies underlying them.

Azpilicueta’s research for other works extends to the construction of masculinity in colonial New Spain, the aesthetics of bondage culture. She also delves into the role of women in Baroque gardens, street slang and historical events such as the women-led ‘Potato Riots’ of 1917 in Amsterdam. Historical figures, such as the lieutenant nun Catalina de Erauso, who escaped a Basque convent disguised as a man in 1599 and pursued a military career in Spanish America, also serve as significant sources of inspiration in her work.

The artist describes the formation of her woven artworks as an open-ended choreography, with compositions continuously being adapted and refined — first on paper, then on the computer, and finally on a weaving loom. The final work often deviates from the original concept. In an interview with Voice Mag, she described working with Jacquard tapestries as “painting with threads,” using up to twelve colours of yarn to achieve a rich palette of 125 hues.

The materials Azpilicueta uses carry their own stories and histories. In her installations, she weaves textiles, ceramics, latex, leather and wax with objects that reference ‘female’ labour and subaltern knowledge — forms of knowledge that have long been marginalised, undervalued or suppressed within dominant power structures and institutions. Azpilicueta embraces techniques such as embroidery, sewing and quilting — traditionally associated with domestic and craft-based knowledge — and repositions them in a contemporary context. In doing so, she challenges institutional hierarchies and advocates for a renewed appreciation of these practices, which are at risk of being lost. By combining artisanal and industrial techniques, she explores how tradition and innovation can coexist and reinforce each other. Azpilicueta’s practice is characterised by collaborations with artisans, performers and researchers, with her textile works often produced in specialised studios such as the TextielLab in Tilburg.

Azpilicueta also draws inspiration from new materialist theories, which emphasise the active role of matter and materiality in shaping the world. In her work, this translates into a thoughtful engagement with materials and techniques that serve not merely as tools but as active, dynamic elements within her practice. This approach invites viewers to perceive materials not just as carriers of meaning but as mutable entities that influence our understanding of both past and present. Azpilicueta works with recycled and natural materials, which add an additional layer of meaning to her objects. These materials bear traces of their form and use, while also pointing to broader themes such as the circulation of resources and the transmission of knowledge — topics often closely intertwined with the exploitation of people and nature.

Azpilicueta's presentation at Art Rotterdam includes the installation "La Fuerza Colectiva", in which a theatrical table with sculptural elements interacts with both space and viewer. Surrounded by plaster hands, the table evokes associations with a spiritual or ceremonial gathering, such as séances or rituals centered around female bodies and shared experiences. The decorative motifs on the tabletop and the vase with an eye motif allude to rituals of female knowledge transmission and collective memory, drawing inspiration from the work of Amalia Domingo Soler, a 19th-century writer, activist and spiritist. These elements reappear in the large-scale Jacquard tapestry "Las Mesas Danzantes", a dynamic visual collage featuring floating objects such as chairs and tables. The tapestry incorporates spiritual and abstract drawings and paintings that were created by Azpilicueta in her early 20s in Buenos Aires, adding a deeply personal layer to the work. It also references the pioneering 19th-century abstract artist Georgiana Houghton, whose exploration of abstraction actually predates Kandinsky — who is traditionally considered the 'creator' of abstract painting. Furthermore, abstraction and spiritism have been closely linked from their inception, for instance in the work of Hilma af Klint. It’s a connection that Azpilicueta explores through contrasting styles and techniques, merging historical prints with delicate hand-drawn and abstract shapes. The resulting work creates a temporary, almost dreamlike space in which the viewer moves between past and present, reality and fiction.

Mercedes Azpilicueta was born in 1981 in La Plata, Argentina, and has been living and working in the Netherlands for several years. She studied at the Universidad Nacional de las Artes in Buenos Aires and earned her Master’s degree at the Dutch Art Institute/ArtEZ in Arnhem. In 2015-2016, she was an artist-in-residence at the prestigious Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. Her work has been exhibited in institutions such as the Van Abbemuseum, the Stedelijk Museum, the Fries Museum, the Barbican Centre and Gasworks in London, IMMA in Dublin, the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, CentroCentro in Madrid, Kunstverein Göttingen and during the Busan Biennale. In 2021, Azpilicueta was nominated for the Prix de Rome, and in 2017 she received the Pernod Ricard Fellowship.

The work of Mercedes Azpilicueta will be featured at Art Rotterdam in the New Art Section, presented by Prats Nogueras Blanchard from Madrid and Barcelona.

Written by Flor Linckens