#MeetTheArtist Sam Samiee

Beauty for the sake of morality in Sam Samiee's Nastaliq series

In the Solo/Duo Section, No Man's Art Gallery shows new work by painter Sam Samiee. In his work, Samiee combines a Western visual language with Eastern narratives and psychoanalytic concepts. Samiee is always looking for shared traditions. He previously found it in abstract work. This time, he focusses on Nastaliq calligraphy. A conversation about the importance of 1001 Nights, transnationalism, Freud's ideas about framing and the Dutch René Daniëls.

Sam Samiee was born in Tehran (Iran, 1988). He completed his residency at the Rijksakademie in 2015 and completed ArtEZ AKI in 2013. Prior to that, Samiee studied industrial design and painting at the University of Arts in Tehran. Samiee won the Dutch Royal Prize for Painting in 2016 and the Wolvecam Prize in 2018. He is currently a member of the jury for both prizes. Samiee’s work is shown internationally and was shown earlier this year at Melly in Rotterdam.

What will you be showing at Art Rotterdam?

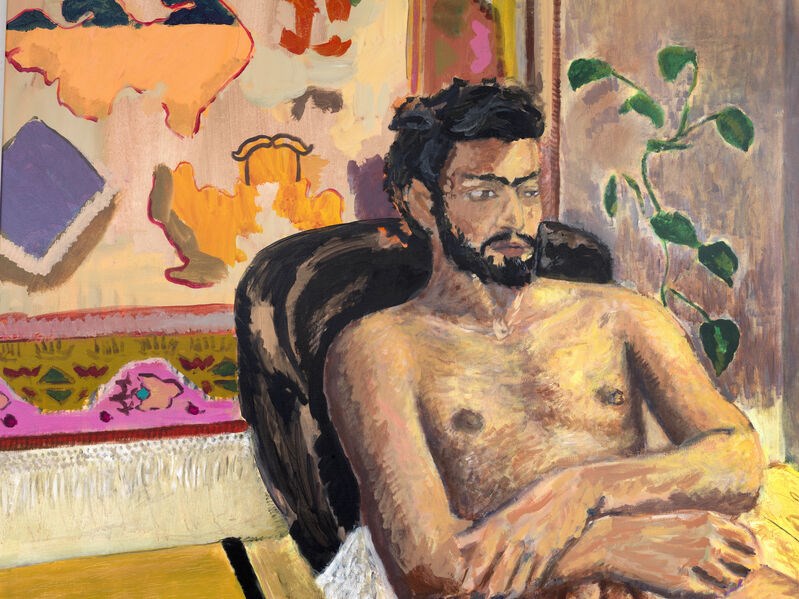

I assume that I will be showing a new work from the series that I'm working on called Nastaliq. Nastaliq is a type of calligraphy which is used mostly in Persian and Urdu. And so in the Eastern Islamic art, not in Western Islamic art, which is more geometrical. The Eastern Islamic world, which includes North India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Kurdistan, tends to use Nastaliq. This is what I'm trying to focus on, on the beauty and representation of groups of people who I don't want to bind them to nation states, to the concept of Iran or Afghanistan.

I would like to signify this group of people with a type of aesthetic that they relate to transnationally. That’s why I call it Nastaliq. In the portrait it might be an Indian boy or an Afghan boy or an or a Kurdish girl or an Armenian boy.

So the series takes its name from eastern Islamic calligraphy, yet the canvasses are painted in a Western style. Why is that?

My education is Western art and in visual arts. So, usually my references are very heavily about Western art history for this series. For the last two to three years, I'm particularly looking at Bonnard more than anybody else, because of his position in European history; postwar, prewar, postwar. As Bonnard, and Matisse too, was an artist who would go unapologetically for decoration. There are also other references to cinematographers and theorists like Pasolini. I think these artists are also looking for a shared tradition that I would say is very related to 1001 nights. I am talking about the usage of aesthetics for the sake of ethics.

You mentioned 1001 Nights and the concept of transnationalism, how are these concepts related and why are they central to your work?

I try to work very discursively based on art history, modes of work. I think in European art history we have well researched intertwined networks of empire and nation states. But when it gets to the intertwined networks of Asia or West Asia, there’s very little scholarship in Europe on art, historical understanding of references or literature of the intertwined networks of Asia, of West Asia.

So I wouldn't like to concentrate too much on Iran, because not only Iran that has these traditions, it's Indo Iranian. It has a lot of Arabic influences, Ottoman influences, Turkish influences, and North African influences too. So, when 1001 nights was translated into Latin in 17th century and then into French and English and other languages it became, as Jorge Luis Borges wrote, transnational. It's not really Persian, it's not really Arabic. It's a shared tradition. I'm very interested in taking something out of the realm of identity politics of one particular group of people. That's why I insist on transnationalism.

Is this also the reason you are interested in abstractionism, because it transcends national or local identities?

Yes, that is correct.

I recently saw your show at Melly in which you tried to escape the traditional frame of a canvas. Why is that important to you?

I’ve been doing this since 2014-15, when I was at the Rijksakademie. I am addressing the very fundamental question of how to deconstruct painting. Again, it was very related to 1001 nights, because 1001 nights is not just a set of stories. It's a programme for framing. How can you produce a frame of a story? Then from within that frame, you enter another frame, and then from that frame you enter another frame. By breaking frames over and over, you also influence the modes of relation within the frame that you are in together with the person who is hearing the story.

This is very similar to the psychoanalytic idea of the frame, because in psychoanalysis Freud produces a mode of relation to the patient, which is not so much about the content of what the patient says, but more about when the patient should come in, when he would lie on the couch, when they finish, what should be the exchange between the analyst and the patient. So the framework as the mode of relationality.

How do you apply these concepts to painting?

I arrived at this question from two ways. One, after the 1970’s, you rarely see painting commenting on architecture. Expect in Europe, except in the work of Constant Nieuwenhuis and COBRA artist. They were situationists. The situation is very much about the architecture, but also about mode of relation, mode of production: who is there, who is playing, who is not playing, who is excluded, who is included. So all these questions relate to the framework.

And through Paul Thek. I think Thek was a great example of a person in seventies and eighties who broke away from the frame of the painting and thought about the painting again within the architecture. More like how Matisse and artists before him would think about painting. But then art history that we studied basically decontextualized painting from the wall. Studying art history we just look at one image.

You rarely see someone like Rothko saying, Well, I want these images to be together. They should be installed in such and such ways. That is why I became interested in the relationship between the painting and where it's installed. And I think as you break the frame a bit by painting on the couch or by painting on the wall, mixing it with painting or any other way, you immediately call into questions of politics and economy and anthropological rituals.

So to summarize it: It touches on the questions of alternative modes of relationality. It poses the question how can we relate differently? In the Melly exhibition, that was why we wanted to have one of the works outside of the room looking like a poster, and we wanted the clouds to move towards the window where it relates to the outside landscape. We wanted the couch to be a condensation of the entire boomgaardstraat and the whole neighborhood. So you have all these relationships in a metaphoric way.

You made a painting about the Dutch painter Rene Daniels as well. Is that also related to his use of space and the interested he had for psychoanalysis?

Absolutely. That painting was a homage to two of his paintings. One of them is called Aux. In it he shows Razi and Ibn Haytham (Alhazen), two Muslim opticians who introduced a theory of optics in the 12th century, and they are connecting an auxiliary cord to this European theory of perspective. It's such a beautiful homage to history of optics and perspective.

Daniels used geometric lines of Islamic art in quite an ironic and funny way, turning it into an auxiliary cord one uses to plug into your amplifier. He’s connecting our Western theory of perspective to that theory of optics that the Islamic world introduced in the 12th century

In my homage I painted a few of my own drawings I chose from my ten years of drawing. I called it Rene Daniels Academy. So he has all these different styles of painting - a Japanese painting, a drawing of a model, a surrealist painting, calligraphy, writing and still life – which brought into a different perspective. And he has also painting of candle and candle is also very common theme in Persian painting. And I have also this.

In an interview with art magazine Mr Motley you mentioned that the Dutch are very much geared to it towards the Anglo-Saxon world and seem to have forgotten about their own past, also when it comes to participation in public discourse. You said wanted to step in, as it were. Was your show at Melly an attempt at participating in public discourse?

I was very satisfied with the experience at Melly. Although I was expecting more media attention considering all the newsworthy questions on the name change (from Witte de With to Melly, ed.), maybe there has been and I yet have to tune in. Now that the painstaking job of archiving is being carried out, other cultures are being recognised for their contribution to Dutch history. With all the contending political ideas, modes of painting and history of painting all merging in Melly, I expected there to be more of a dialogue. I think we are drawn to the Anglo-Saxon world because they do a great job, meaning that they have a specific history in shaping museology. They put things out there and say with confidence: this is the way.

Since you're interested in politics or political discourse, I was wondering if you are working on something reflecting the current events in Iran?

I think becoming an artist itself is so political, even if you don't necessarily show politics. I think 1001 nights is one of the greatest political positionings in the history of Iran. 1001 nights is an example of politics by artists in Persia. How to use beauty to introduce ethics.

Also, at some point you realise that the excess of catastrophes exceeds your capacity to capture screenshots of history. Therefore, you must produce something that is not journalistic because journalism on Iranian politics is gone by the wind every day. Some 70, 80 days have passed since the revolution. There are 2 to 3000 important points and letters and pieces that can be curated. As an artist, what can you do?

We need to produce works that transcend all this in order to create an analytic space to think and be political. I don't produce political content. I produce the space within which political thinking should become possible, and I think that should be my role as an artist.

So, the politics is in the form and context?

I think my position was always to use aesthetics. Formalism and beauty and decor, uncertainty and to think of what will remain and keep things together.

So my Nastaliq paintings are just as political as Rene Daniels was. He decentralizes Europe in European art history, that's as political as when you paint a Muslim Indian boy who is now under the fascist state of India. Also, I think Pasolini’s film 1001 night was dealing with fascism as much as his Salo was. Bonnard was purposefully distancing himself from avantgarde artists because he realized its machismo was feeding fascism. He opted for a more feminine and decorative approach instead.

All of these were political positions. It's just that our art, our art history hasn't touched on it as such, and our institutions haven't managed to take a strong position on them. Maybe there are some institutions have, and some have not. So, I don’t think that as one artist I can do the Herculean job of changing the narrative for everyone.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel