Figuration or abstraction is ultimately a matter of scale

Interview with Filipp Groubnov

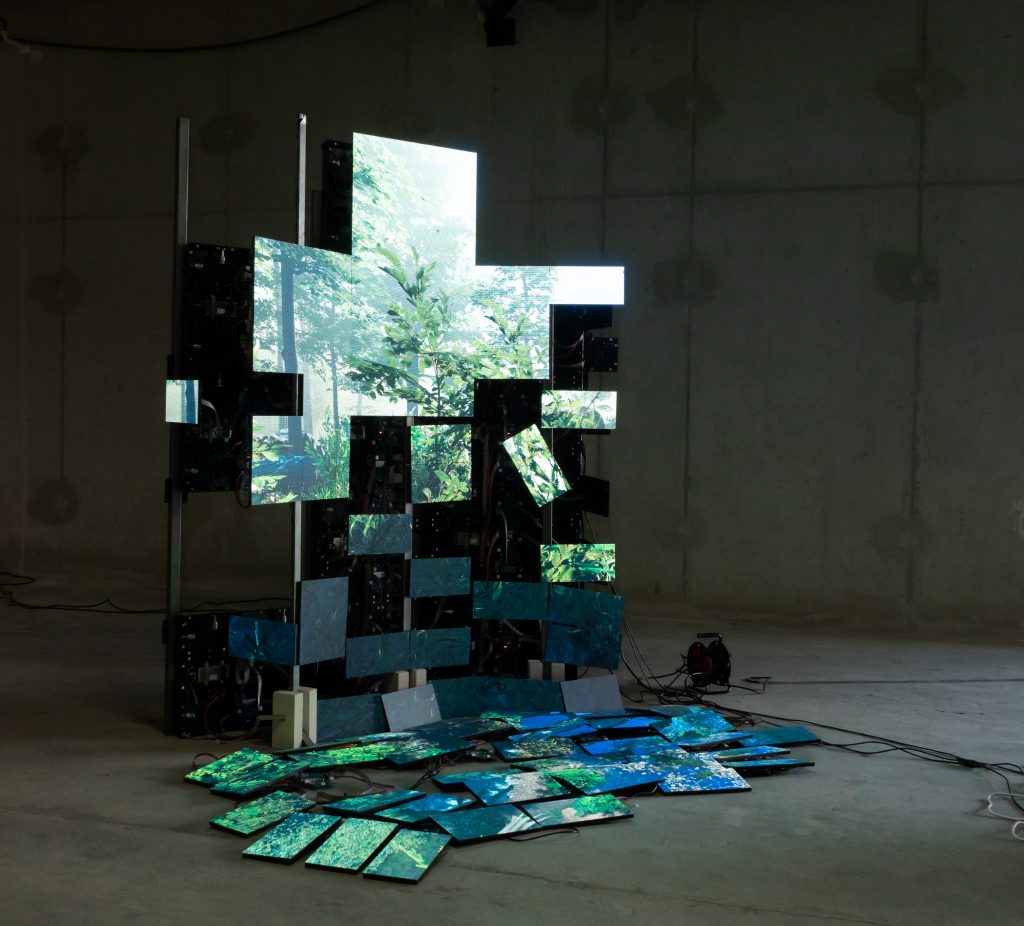

Eight years ago, Filipp Groubnov moved from Belarus to the Netherlands. At the Royal Academy in The Hague he discovered that he could express many of his interests in installations. He prefers to be in the border area of various artistic and scientific disciplines. “There I find space for my own story and the opportunity to discuss all kinds of questions that occupy me. There are simply too many things that inspire me to put them in a single system.” This also applies to his visual language, which is a unique mix of figuration and abstraction, although according to Groubnov this is ultimately a matter of scale. His work is shown at Art Rotterdam by Josilda da Conceição.

Let’s start at the beginning. Before studying fine arts, you studied physics. What made you switch?

Even before studying fine arts, I was very interested in art. I have always been involved in some sort of creative activity, from graffiti to drawing and painting. I think the main reason why I didn’t choose to study art initially was because I didn’t know anyone who followed that route and, at the time in Belarus, I didn’t really consider an art career as a possibility. On the other hand, I was interested in science and I imagined studying physics as a kind of creative process, too. But one year into the programme, I realised that it was very formal and uninspiring. At some point, I simply couldn’t do it any longer and that’s when I decided to switch.

You moved from Belarus to the Netherlands in 2015. What kind of work were you making at the time?

When I moved to the Netherlands in 2015, I wasn’t very familiar with contemporary art. In fact, I was barely familiar with contemporary art at all because it isn’t well represented in Belarus. At the time, there was only one gallery that showed contemporary art in Minsk and I also lacked a context to truly understand it. I was mostly influenced by early 20th and 19th century styles like Impressionism and Surrealism, and was mostly focused on painting and drawing.

Would you say there’s a different approach to art here than in Belarus? If so, was it hard to get used to?

It was definitely hard to get used to the idea of ‘contemporary art’ and what it entails. I often struggled to understand what the teachers expected from me and was also missing a huge number of cultural references since around the 60s. So, it definitely took some time to catch up, but I feel like it also gave me a unique, almost ‘outsider’ perspective to contemporary art.

Your work isn’t political in nature. Given the mass protests after the 2020 general elections in Belarus and the war in Ukraine, as well as the role of Belarus in this, I can’t help but wonder if it is hard to stay away from politics in your work?

For a long time, I’ve had this idea that I wanted to stay away from ‘politics’ in my work, but this is changing, especially due to the events that you mention. I think that I no longer consider ‘political’ as something separate from other facets of life. It is just part of the condition that shapes many complex relationships between human, matter, mind, etc. In my last work, for example, my personal story and the current situation in Ukraine becomes part of the narrative and an essential element of the project.

I’ve read that you started out by painting on canvass. Today, you primarily make installations. What happened along the way?

That’s right, my more ‘conscious’ artistic journey started with canvas and oils. The switch to sculptural installations happened while studying in the Netherlands. I was enrolled in a course on ‘expanded sculpture’, which inspired me to experiment with installation and different media. You might say it opened my eyes to the fact that sculpture and installation can be so many different things. I then began to be aware of all the possibilities to combine materials, images and sounds. I slowly starting realising that in the field on installations, I can combine all my interests in one. To this day, I am in awe of all the possibilities of installations. I still feel like I have only scraped the surface of this discipline.

What would you say is the main theme of your work?

I think an essential (central?) theme of my work is to reject the idea of a ‘main theme’. My interest is in multiplicity and approaching any subject as a kind of choir of detuned, human and non-human, living and non-living voices. What I choose to talk about changes from one project to the other, but what stays the same is my approach to positioning things like personal emotions and narratives in the same ensemble as, for example, the erosion produced by water passing through the landscape. Right now, I am quite fascinated by the subject of war and violence, but it is really through the relationships and interactions I create between the story and different materials that the subject unfolds in front of me and takes on all the complex facets that bring it to life.

Your installations have a mix of abstract and figurative elements. How did you arrive at this visual language?

This developed very organically. I think because, on one hand, I am interested in rather ‘abstract’ concepts like those found in physics and science and, on the other hand, I am also very interested in personal and concrete experiences. Ultimately, my approach is that there is no absolute distinction between what can be called ‘abstract’ and ‘figurative’. In physics, for example, we can imagine ‘particles’, which are described in classical physics as discrete concrete entities. But, if we consider the very small scale described in quantum physics, these particles are more like a very abstract ‘field’ without any clear boundaries. So, figurative or abstract may merely be a matter of scale.

How do you go about assembling your installations? Do you have a preconceived idea and then find the right attributes or do you work with whatever happens to be around?

Every installation is a combination of the two. I like to juxtapose some very meticulously crafted elements with ready-made and sometimes more ‘random’ objects that I find. For example, in the installation The Garden of Iarthly Delights, I have placed together a sculptural head of Narges Mohammadi with construction material from a shop. While the construction material was something you can easily buy ready-made, the head on the other hand was a result of a long process of 3D-scanning Narges, 3D-printing the model, casting it, etc. I find the combination of deliberate and spontaneous actions very enriching for the work.

Some of your work has titles that refer to philosophy and biology, such as Natural Philosophy and The Garden of larthly Delights. Are philosophy and biology the main sources of inspiration for you?

In a way, yes, but I think that ‘philosophy’ and ‘biology’ sound so formal. Both of these disciplines are a way of studying phenomena, a systematic approach to research and communication. I am mostly interested in researching areas where these systems start to lose their solid foundation. Within the blurry boundaries of disciplines and systems, I find space for my own story and all kinds of questions that intrigue me. But at the end of the day, there are too many things that inspire me to put them in a single system.

Your installation The Garden of larthly Delights contained living species. I can imagine it can be hard to display in a presentation. So, why do it?

Yes, you are very right. Working with living organism is quite challenging within the context of art exhibitions, which are normally geared towards a different kind of art experience. Most art (or, more specifically, fine art) spaces have a tradition that is based on art objects being static, inanimate ‘beings’. In that context, presenting a living creature requires a completely different set of rules. I find that tension very interesting and it opens up new ways of thinking about art as active participants in the space.

Congratulations on your presentation at Art Rotterdam! What can we expect?

Thank you! Currently, I am working on a project in collaboration with Highlight Delft festival and New Media Center of TU Delft. It revolves around the subject of war and the area of France where the ‘Great War’ left a lasting mark on the landscape. You can expect to see new work with a combination of a digital post-war environment shown on screens and physical sculptural elements. I don’t want to reveal too much because, as a visual artist, I always believe it is better to see for yourself than to hear an explanation. I am also experimenting with glass paintings that might find their way into the final presentation.

Right now, you are at the start of your career. What do you hope to have achieved in the next five years?

There are a lot of things I want to achieve or get involved with. I really hope to participate in residencies that can give me a chance to work with researchers or scientific institutions. I am very interested in interdisciplinary collaboration and, right now, one of my main goals is to establish such partnerships. I would also really like to present my work in more international venues. I have interacted with Dutch audiences for some time now and I am very curious to see how people from other countries and cultural backgrounds interact with my work. I think that would teach me a lot.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel