Rethinking Gaming and Technology: A Conversation with Janne Schimmel

Through his work, artist Janne Schimmel (b. 1993, The Netherlands) bridges the digital and physical worlds, exploring gaming and technology from a fresh perspective. This year, he is presenting Between Modder and Mud (2024) in the Prospects section of Art Rotterdam, a gaming sculpture featuring a self-designed game that invites interaction and reflection.

What is the common thread in your work?

“Gaming has always played a role in my work,” Janne explains. “What fascinates me is the contrast between how game worlds are designed and how gamers shape their physical spaces. Take World of Warcraft, for example: a richly detailed, magical world filled with crystals and spiritual elements. Yet, the typical gamer’s room is often minimalist and sleek, with LED lighting, streamlined furniture, and cold, industrial consoles. These two worlds are in stark contrast, and in my work, I aim to bring them together.”

His sculptures expose this tension and challenge the conventional design of gaming hardware. “The devices we rely on to connect with the digital world are often designed to convey power and speed, while softer, more emotional qualities are rarely considered. I want to change that narrative.”

Why is gaming hardware and design often so limited aesthetically?

“I think it stems from our performance culture,” says Janne. “In the 1990s, during LAN parties—gatherings for computer enthusiasts—gamers would come together to showcase the fastest and most powerful computers. They would open the side panels of their cases to proudly display the hardware inside. This led to an aesthetic centred around components that exude strength and speed.”

In his sculptures, he literally exposes these components—motherboards, processors, and graphics cards—but contrasts them with materials such as crystals, jewellery, and stones. “By placing these opposing elements side by side, I want to highlight how narrow the aesthetics of gaming hardware have become and create space for something softer, something less rational.”

He also sees the influence of patriarchal structures in this. “The idea that hardware must be powerful and masculine leaves little room for emotions and softer aesthetics. A lot of these traditional ideas are still deeply ingrained.

Gaming is often seen as a solitary activity, but in your work, you highlight the power of gaming communities and user-generated content. Can you elaborate?

“Gaming is much more than an individual experience,” Janne emphasises. “The strength of communities lies in the sharing of knowledge and creativity. A great example is the modding community, where gamers modify existing games. This started in 1993 when the developers of Doom made their code public, allowing players to make their own modifications. That moment changed the industry forever.”

Janne also speaks highly of the homebrew community, where people create entirely new games for old consoles like the Game Boy or Nintendo DS. “What I find so inspiring about this is how the community reactivates outdated technology and challenges the commercial gaming industry. But perhaps even more importantly, they create space for their own stories. The mainstream gaming industry is still dominated by white men, who tend to tell a very singular type of narrative. Homebrew creators break through that. In doing so, they rewrite and repair the stories that are being told.”

These communities are a direct source of inspiration for Janne. He also incorporates their shared techniques and code into his own games. On his sculptural consoles, visitors can not only play his self-made games but also games created by others in these communities, such as LesbiAnts, Toni Catino, a game about lesbian ants. “Just the title alone is genius,” he laughs. “It’s the perfect example of a story that would never emerge from the mainstream industry. These kinds of games show why these communities are so important.”

How has the Mondriaan Fonds grant influenced your work?

“The grant gave me the freedom to explore my creative processes in greater depth,” says Janne. A significant part of the funding was used to invest in a CNC machine, which allows him to cut digital designs with organic shapes into wood and other robust materials with extreme precision. But what fascinates him most is that the process does not end with the physical form.

"I first turn my digital designs into physical 3D objects. Then, I scan those objects back into a digital model and share them with the community. They can integrate these models into their own designs or 3D print them, bringing them back into the physical world. This creates a continuous exchange between the digital and the physical."

This principle of reuse is also reflected in his design pieces. “One of my sculptures started with an IKEA chair I’ve had since I was 11 years old. When the armrest broke, I repaired it by casting a new one in aluminium. That repair later inspired the sculptural forms of my design chairs and benches.”

What will you be showing at Art Rotterdam?

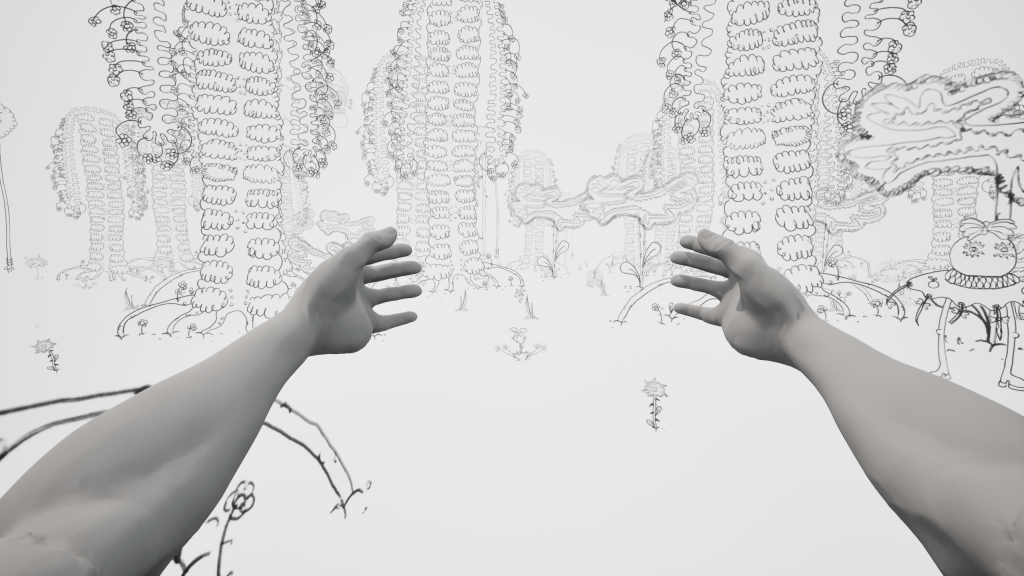

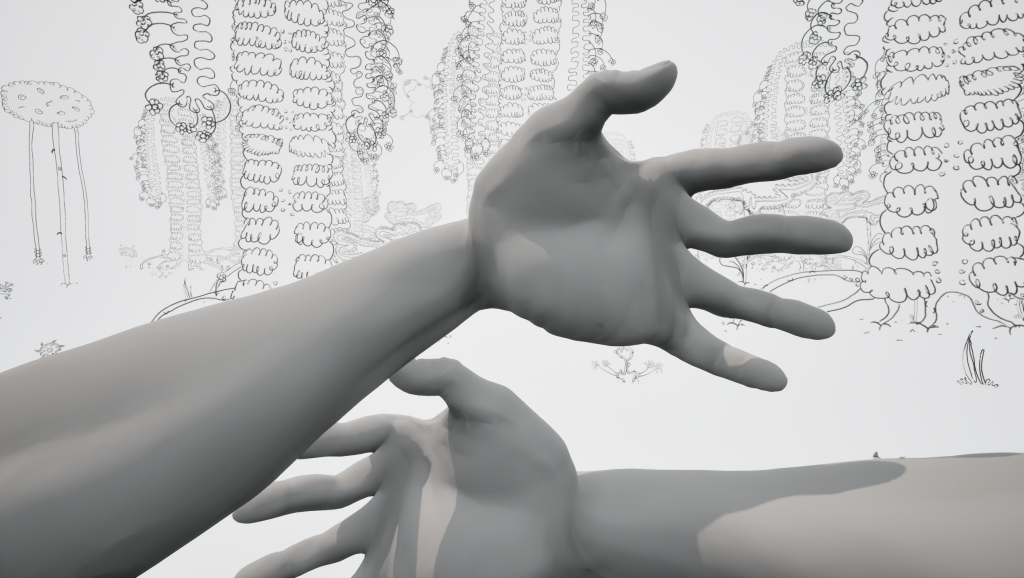

At the Prospects section of Art Rotterdam, Janne is presenting Between Modder and Mud (2024), a gaming sculpture where visitors can play his self-developed game First Person Hugger (2024).

“I wanted to create a game where compassion takes centre stage. In many commercial games, violence is a central element, and I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing,” Janne says. “I grew up with it too, but if I were to create the same thing now, it wouldn’t add anything new. In First Person Hugger, you don’t see the world through the barrel of a gun, as in a traditional first-person shooter, but through open arms. Instead of shooting, the player’s main interactions are hugging and talking.”

This idea was sparked by a moment that has always stayed with him. “I was gaming as a teenager when my mother walked in. She saw a bouquet of flowers in the game and said, ‘Give those flowers to a woman.’ But the only thing I could do was use them as a weapon. That made me realise how limited in-game interactions often are. I want to create something that offers a completely different perspective.”

Written by Emily Van Driessen