Coming soon

Coming soon

Select type

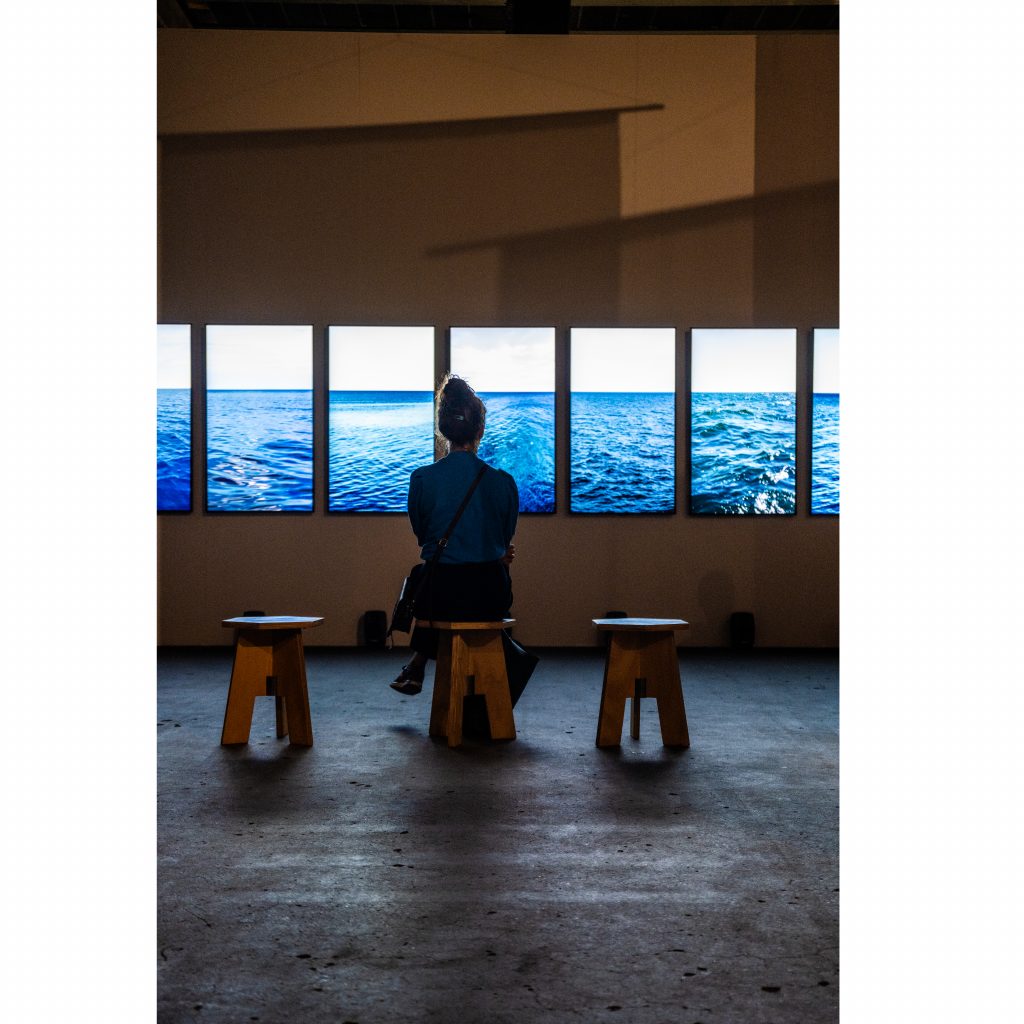

The thirteenth edition of Unseen, now part of Art Rotterdam, will take place at the end of March 2026 — and not, as previously announced, this coming September at Amsterdam’s NDSM Loods. Unseen and Art Rotterdam are joining forces and are currently preparing for their first joint edition, scheduled to take place from March 26 to 29, 2026, at Rotterdam Ahoy. Like Art Rotterdam 2025, this combined edition will cover an area of 14,000 m².

In recent years, Unseen has been confronted with a diminishing role of photography within gallery programs and a declining number of galleries exclusively focused on photography. The strategic alliance with Art Rotterdam opens new doors for Unseen: a compact, carefully curated and sharply focused selection of photography within a broader contemporary art context.

Art Rotterdam, widely praised as an experiential fair with a variety of sections under one roof — including video art, sculptures, and large-scale installations — will become even more diverse and appealing to a young and international audience through the addition of a strong photography section.

A stronger platform for photography

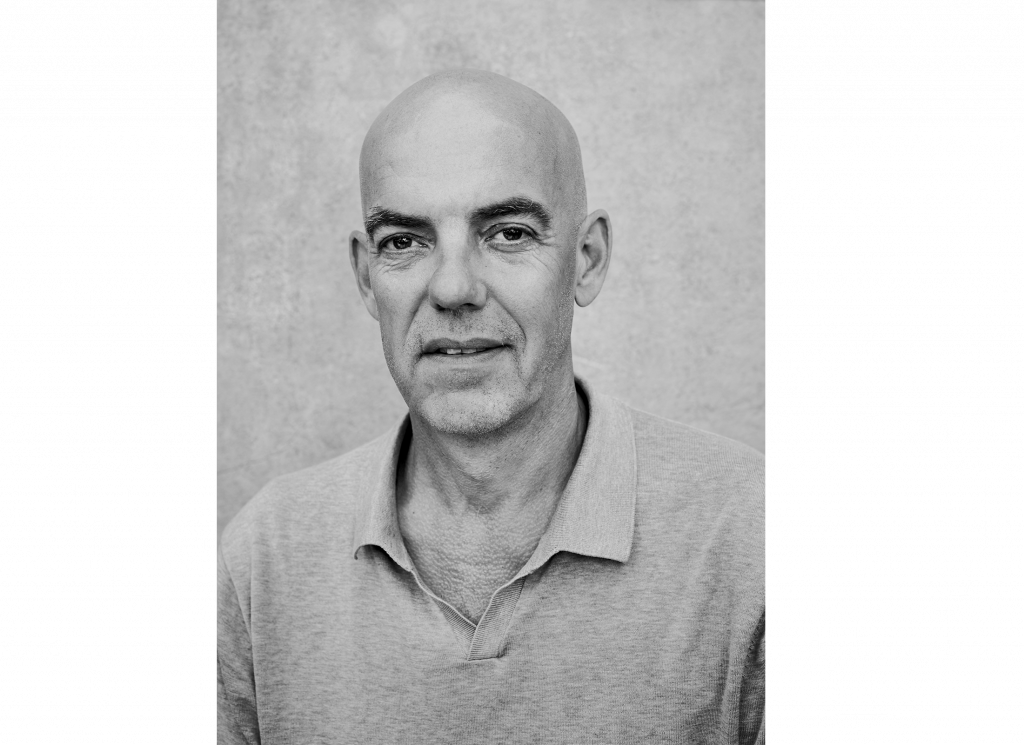

Fons Hof, director of Art Rotterdam and Unseen Amsterdam:

“Especially in a time when the photography market is facing challenges, the integration of Unseen into Art Rotterdam offers a unique opportunity for renewal. This creates a more powerful platform that strengthens photography as an essential voice within contemporary art.”

Benefits of the new joint setup

In addition to benefiting from Art Rotterdam’s visitor flows and promotional efforts, Unseen will maintain its focus on international collectors, curators, and photography professionals. In collaboration with the fair’s curators, Unseen is developing several special programs. The reopening of the Dutch Photo Museum in the iconic Santos warehouse in Rotterdam will play a prominent role in this context.

Moreover, Unseen’s social media channels (92,000 Instagram followers) will remain exclusively focused on photography presentations. This ensures additional exposure for the selected Unseen works during Art Rotterdam. The strategic merger offers photographic talent a broader platform.

Unseen’s unique identity and mission — to discover and support emerging photographic talent — will remain central and will be further sharpened within the multidisciplinary framework of Art Rotterdam.

Unseen Book Market

At present, the organization is exploring in what form the much-loved Book Market component can also relocate to Rotterdam. Discussions are ongoing with various partners about a suitable venue in the city.

Director Art Rotterdam Fons Hof about the move to Rotterdam Ahoy

For its 26th edition Art Rotterdam is moving to the Rotterdam Ahoy, the event centre in Rotterdam South. Fair director Fons Hof immediately saw the potential of the spacious new venue. Alongside Prospects, which was the main reason for the move, Projections, Sculpture Park and Intersections will also be returning at the Ahoy. “It will be a total experience. We’re showcasing a versatile spectrum, from more collectible art to institutional work,” Hof says.

“There aren’t many locations in Rotterdam that are 10,000 square meters or larger—in fact, there’s just one,” Hof explains as the decision why they choose the Ahoy. When it became clear that the distribution hall of the Van Nelle Factory would no longer be available from 2025, the decision came quickly. Prospects, the section for young artists supported by the Mondriaan Fund, has traditionally been housed in this hall. Losing this section would directly impact Art Rotterdam’s identity as the fair for young art.

“It’s not an architectural monument, but we’re getting so much in return. People are familiar with the Ahoy Arena from concerts and the tennis tournament, but we’ll be in the exhibition halls, which have been completely renovated, and a concert hall—the RTM Stage—has also be added. The venue also has a fantastic mix of natural and artificial light, which pleasantly surprised us.”

“Art Rotterdam had outgrown the Van Nelle Factory,” Hof adds. The narrow entrance often caused bottlenecks, parking was limited and there were not enough options for food service. “At the Ahoy, we’re ‘small fry’,” says Hof, noting Ahoy’s larger capacity.

Broader concept

Hof immediately recognised the opportunity to broaden Art Rotterdam’s fair concept. At the Ahoy, there is plenty of space for Prospects, which will also be significantly larger. And the Sculpture Park, Intersections (large-scale work) and Projections (video art) sections are all making a comeback. All three had occasionally been excluded in previous editions due to space limitations. “It will be a total experience. We’re showcasing a versatile spectrum, from more collectible art to institutional wors,” Hof emphasises.

The revamped setup also caters to a new generation of art collectors. Instead of a small group purchasing large quantities of art, there is now a broader range of buyers who make smaller purchases. This group seeks out information about all facets of the art world. “People are interested in a day out, and good food is part of that. At the Ahoy, the food and beverage offerings will triple, including a pop-up restaurant by Café Marseille, famous in Rotterdam for its delicious and honest French cuisine.”

“Art fairs are always looking for ways to make their concept more engaging. We’ve found the key,” Hof adds. He presented the new concept to international galleries, which responded enthusiastically. The number of international participants increased from one-third to half. In the New Art section, dedicated to young galleries, 80% of participants are from abroad. This is partly due to the internationally acclaimed curator of the New Art section, Berlin-based Övül Durmuşoğlu.

Connecting with Rotterdam South

Art Rotterdam has always emphasised strong ties with art institutions and initiatives, while valuing an excellent relationship with the city. The move to Rotterdam Ahoy also signifies a shift to Rotterdam South, a part of the city that the municipality aims to develop further. Like Art Rotterdam, the new main sponsor, Rotterdam-based DHB Bank, prioritises a strong connection with the city. In the new DHB Art Space, curated by Rotterdam collective Unity in Diversity, Pedro Gil Farias will be creating a sound artwork featuring the dreams of Rotterdam South’s residents, further linking the art world to the local community.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel

The New Art Section is arguably one of the most exciting components of Art Rotterdam. This year, curator Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu has brought together a surprising mix of international galleries, each presenting a solo booth by artists proposing new formal and material languages. The section welcomes galleries and artists of all ages, making it a unique space for visitors to discover various paths artists choose to challenge the status quo.

Curator Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu brings her extensive international experience and sharp vision to this dynamic section. With an impressive background in both biennials and exhibitions, and a profound commitment to intersectional and feminist perspectives, Durmuşoğlu focuses on creating an environment where diverse artistic voices and innovative ideas converge. Under her guidance, the New Art Section not only serves as a refreshing constellation of artists but also poses critical questions about what ‘new’ truly means in a time of significant social and cultural transformation. In an interview, Durmuşoğlu shares her vision, curatorial approach, and the exciting collaborations featured in this year’s New Art Section.

Can you describe your vision for the New Art Section? How have your experiences across different contexts — ranging from biennials to monographic exhibitions — and your engagement with topics such as intersectional futures and togetherness (from feminist queer perspectives) shaped your approach to curating the New Art Section? What do you hope audiences take away from experiencing your approach?

The world has been going through a major and painful wave of metamorphosis since 2020. Some call it the time of monsters, after Gramsci and Baumann, some think liberalism is already dead and nobody claims its corpse. Questions need to be definitely reformulated, solutions need to be collectively shaped. Freddie Mercury already asked back in 1991: ‘Does anybody know what we are living for?’

As a curator who has been working on collective memory of struggles, intersectional futures and togetherness, I am personally curious about what stays behind and what flourishes new after this giant tide subsides. So the New Art Section takes a questioning spirit; what is that new we have kept running after? What versatile languages can be built inside that questioning spirit?

My desire for the audiences of is that they leave with curiosity, imagination and hope through the constellation of diverse artistic voices and positions we present in the section. There are many worlds in the world that co-habit alongside each other and art world is the same. Creating meaningful environments of relation and communication, rather than division and separation, is crucial in all settings of artistic presentation, including the market.

What excites you most about this edition of the New Art Section? Could you highlight any artists that particularly resonated with you during this year’s selection process?

First of all, I am excited to bring my fair experience from working with ARCO Madrid to Art Rotterdam: It is an organisation that means a lot for local and regional actors and that has a promising potential of growth beyond the region. New Art Section serves as a vital stepping stone environment for upcoming galleries, providing them with a platform where they get to fine tune their voices alongside marking the global young positions connected to the Dutch art scene.

Mercedes Azpilicueta, who has chosen Amsterdam as her second home after Buenos Aires, will be showing her work at Art Rotterdam for the first time. [Her work was recently on view at the Stedelijk Museum, ed.]. Thanks to the gallery Prats Nogueras Blanchard, we will present her mind bending humorous work that challenges everyday understanding of corporealities. On the other side, Brussels-based artist Yesim Akdeniz, who showed her paintings in Art Rotterdam fifteen years ago, comes back with exquisite installation work departing from eccentricities of modernist logic.

A long time friend and collaborator Ivan Gallery from Bucharest comes with the strong and delicate painting work Shahin Sharafaldin for the first time, who currently lives in London. I am also very happy to be able to present the fresh and uncompromising work of Mane Pacheco with Balcony Gallery from Lisbon, an artist that I have been following for a while. Thanks to KIN, one of the new voices of Brussels, it was exciting to discover the work of Tanae Hynes, questioning the illusions of liberal logic, which is echoed by Buenos Aires-based artist Nina Kovensky, presented by Quimera.

You have been working in different institutional settings throughout your internationally driven practice alongside the fair structures. How do you see the interplay between the commercial art world and experimental and critical art practices?

Always curious about infrastructure as material and notion, I believe it is important to acknowledge the dynamics of art world’s different components in order to propose better working solutions. The balance among galleries, project spaces, initiatives, art centres, and museums in a particular context shows a healthy and sensitively woven artistic structure. Therefore, in a world that pushes us to respond only in like and dislike, love and hate, I propose to search after meaningful pluralities and a fair share of resources.

What are you currently reading and watching?

I’m currently reading the English translation of Aimé Césaire’s long poem ‘Return To My Native Land’ (1956), whose thinking has kept on inspiring me, about the measure of the world, radical hope and the irony of projected equality for humanity. ‘The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages’ (2013) by François-Xavier Fauvelle is so refreshing to read, Fauvelle treats the unspoken histories of civilisation in such a careful and intelligent way. I am also accompanied by the new jewel biography of Audre Lorde penned by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, ‘Survival is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde’. I have watched the works of Pinar Ögrenci and Claudia Pages Rabal for the new texts I am preparing and Kamal Aljafari’s precise counter narrative take ‘A Fidai Film’ (2024).

About

Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu is a curator, writer and educator with a focus on constructive critiques of civilization, the sustainability of intersectional futures, and practices of togetherness from feminist queer perspectives. She recently curated the monographic exhibitions ‘The Story Behind Each Word Must Be Told’ by Nil Yalter (Ab Anbar, London), ‘Portrait of a Movement’ by Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz (CA2M, Madrid and Tensta Konsthall, Stockholm), and ‘Burn&Gloom, Glow&Moon: Thousand Years of Troubled Genders’ by Katrina Daschner (Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna). She also co-curated two editions of the Autostrada Biennale in Kosovo and in the past curated programmes for the Istanbul Biennale, dOCUMENTA (13) and steirischer herbst. Durmuşoğlu co-leads the Art in Discourse programme at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig and previously taught as a guest professor at the Graduate School of the Universität der Künste in Berlin. She lives and works in Berlin.

New Art Section 2025

The galleries participating in the New Art Section in 2025 are: Balcony Gallery (Portugal), Brinkman & Bergsma Contemporary Art (The Netherlands), BUYSSE GALLERY (Belgium), Contemporary Cluster (Italy), Double V Gallery (France), Erika Deák Gallery (Hungary), Galerie Fleur & Wouter (The Netherlands), Galerist (Turkiye), Gallery Van Fanny Freytag (The Netherlands), Ivan (Romania), JOEY RAMONE (The Netherlands), Kin Gallery BV (Belgium), Mini Galerie (The Netherlands), Pizza Gallery (Belgium), Prats Nogueras Blanchard (Spain), Quimera (Argentinia), SANATORIUM (Turkiye), TATJANA PIETERS GALLERY (Belgium), Wouters Gallery (Belgium) and Zyrland Zoiropa (Germany).

Written by Flor Linckens

For the ninth consecutive year, the NN Art Award will be presented in 2025 to a promising artist showcasing their work at Art Rotterdam. This year’s nominees are Diana Scherer (andriesse eyck galerie), Marcos Kueh (Prospects section of the Mondriaan Fund, courtesy of Galerie Ron Mandos), Pris Roos (Mini Galerie) and Bodil Ouédraogo (Prospects section of the Mondriaan Fund). The work of the four nominees will be on view at Kunsthal Rotterdam from 15 March until 11 May 2025.

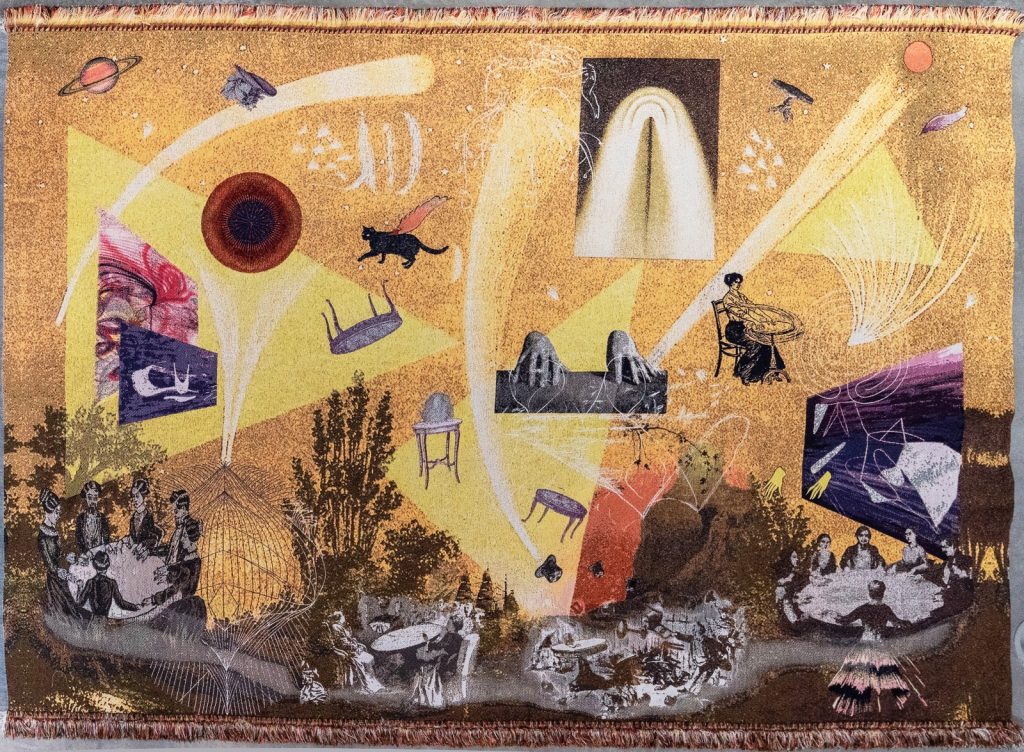

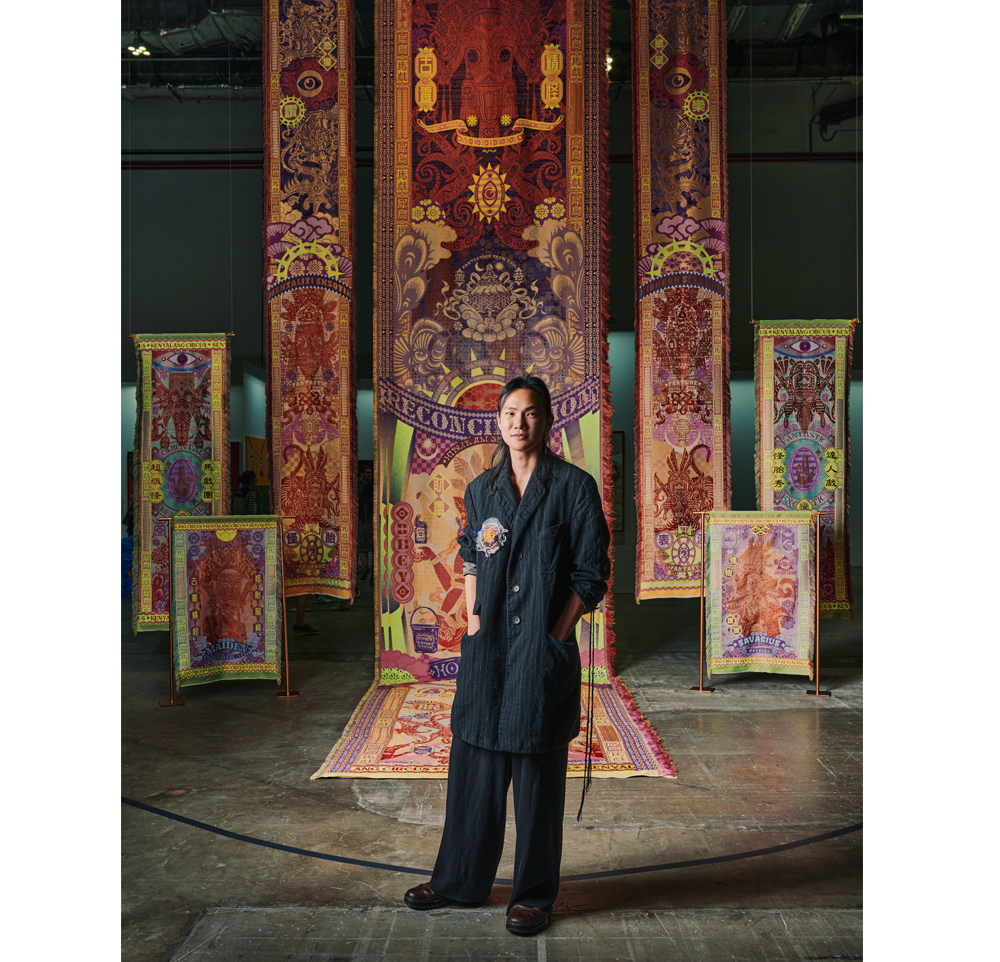

Marcos Kueh (1995) explores the intersections of heritage, identity and contemporary visual culture through his textile-based practice. His woven installations serve as vessels for storytelling, blending traditional craftsmanship with contemporary themes and techniques. At the heart of his work lies an inquiry into the role of textiles as a medium for historiography and self-reflection.

Kueh grew up in postcolonial Malaysia, in the Malaysian part of Borneo, where the legacy of colonial influence, exoticisation and cultural displacement remains deeply embedded. This layered history is central to his artistic practice. Initially, Kueh studied graphic design and advertising at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, but it was only when he began exploring textile design at the same institution that he recognised the potential of textiles as a form of expression. He became fascinated by how his ancestors in Borneo wove stories, myths, and dreams into intricate patterns. This discovery led him to merge traditional weaving techniques from Borneo and other Southeast Asian regions with contemporary Western industrial methods, forging a dialogue between past and present. Beyond its narrative potential, Kueh is also deeply invested in the technical precision and craftsmanship inherent to textile-making.

His work engages with self-awareness and the complexities of decolonisation: both as a historical process and in the ways it continues to shape personal and collective identities. While studying in the Netherlands, he first encountered academic discourses on decolonisation. This experience gave language to a longstanding sense of injustice he had struggled with, revealing it to be not only personal but also systemic. Kueh juxtaposes constructed representations with his own lived experience, interrogating the persistent colonial and postcolonial narratives that continue to shape identity in Southeast Asia. He raises critical questions about terms like ‘Third World country’ and examines who holds the power to narrate the histories of formerly colonised nations. He points out that in Western academic contexts, decolonisation is often framed as a theoretical concept, while the voices from formerly colonised regions — those who originally led decolonisation movements — remain underrepresented. Through his textile works, Kueh confronts these dynamics. His practice bridges personal lived experience with academic reflection, examining how we shape and understand our own histories. He observes that Malaysians often neglect their own stories and history, while unconsciously internalising the colonial gaze that was once imposed upon them.

At Art Rotterdam, Kueh (courtesy of Galerie Ron Mandos) will present a work in the Prospects section of the Mondriaan Fund, delving deeper into the layered nature of identity and cultural heritage. Originally developed for Manifesta 15, this installation was previously exhibited in a 17th-century church in Barcelona, where it engaged in dialogue with a Christian altarpiece — an emblem of the religion introduced to Malaysia by European colonial powers under the guise of ‘civilisation’. In this work, Kueh visualises the inner tension of a postcolonial identity: the struggle between assimilation and authenticity, between adaptation and resistance. In doing so, he dismantles the colonial legacy of Catholicism in Borneo in a way.

Beyond the historical and political dimensions of his work, Kueh also examines how mass communication and advertising shape cultural representation. He draws parallels between traditional storytelling systems and contemporary marketing strategies, exploring how visual communication can manipulate or instrumentalise cultural identity. His woven billboards construct a fictional world where textiles function as a form of visual propaganda, commenting on the ways in which identity is consumed, redefined, and eroded within the capitalist system.

Kueh invites the viewer to look beyond the aesthetic qualities of textiles and instead engage with the deeper structures of history, identity, and craftsmanship embedded within them. At the same time, he infuses his work with humour and satire, perhaps to make the medicine go down easier or to start more meaningful conversations. By interweaving contemporary myths and legends with Sarawakian motifs, symbols, and figures, he creates an alternative mode of visual storytelling.

Marcos, could you tell us a bit more about the work you’re presenting at Art Rotterdam and in the Kunsthal?

Kenyalang Circus is a long term project I started in 2016, that speaks about the exotification of my identity as a person from Borneo. From anthropological museums to tourism advertisements, how we are being described becomes how we describe ourselves, becomes how we perform to the people who wrote our descriptions. The giant woven posters and billboards in these series usually depict images of creatures manifested from stereotypical ideas of the mysterious unknown of the Borneo rainforests. My job, as the ringmaster of the circus, is to parade them around and try to “sell my exotic identity”. The circus has travelled all over the world in many iterations and this will be our debut in Rotterdam.

The work “Homo Reconciliation Eternatus”, originally commissioned for the 15th Manifesta Biennale in Spain, will be performing at the Prospects section of Art Rotterdam. It speaks about the internal struggle to love ourselves and find pride as people from developing countries. “Nenek Moyang”, which debuted in ART Singapore, will be showcased in Kunsthal Rotterdam. The 8 meter woven billboard is displayed like a waterfall – a nod to the Bornean myth in which the ancestors who live in heaven would only travel to the earthly realms through the waterfalls. The high display also prompts viewers to practise looking upwards to your own culture.

What are your plans for 2025?

In 2025, I will be attending a few residencies for the first time as a professional artist. Many of the project plans have been naturally progressing into conversations about factory work. As a Chinese-passing [a person often perceived as Chinese based on their appearance, ed.] non-European person who is deeply involved in the Dutch textile industries, I am excited to dive into stories and conversations about class, capitalism, migration and identity on the factory line. My work has always been about textiles as a finished product, so it is interesting to expand my exploration into the systems surrounding this production. Hopefully by this time next year, I will have many meaningful stories to share.

Can you describe how you felt when you heard you were nominated for the NN Art Award?

I was in Malaysia when I received the news and immediately went to grab some food with my family to celebrate. I’m just glad that there are people out there who consider my work valuable and am glad that by chance, my family was close by to share in the joy.

If you were to win the award, which project would you immediately pursue?

The award will definitely open up new possibilities on my upcoming research projects into factory work and allow me to consider more locations to visit, plus more people to talk to. In a way, the award has already given me so much spotlight, I am also hoping to bring that light forward to undiscovered stories, conversations and perspectives of labourers who we normally can’t interact with in our day to day lives.

At Art Rotterdam, Kueh’s work will be on view in the 13th edition of Prospects, an initiative by the Mondriaan Fund. This exhibition presents work by 116 artists who received financial support in 2023 to aid them in the start of their careers. The section is curated by Johan Gustavsson and Louise Bjeldbak Henriksen. Explore all Prospects artists here.

Marcos Kueh was born in 1995 in Sarawak and divides his time between the Netherlands and Malaysia. In recent years, his work has been exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum, Kunstinstituut Melly, Manifesta, The Backroom in Kuala Lumpur, and Museum Voorlinden. In 2022, he was awarded the Ron Mandos Young Blood Award, after which Museum Voorlinden acquired one of his works. Joop van Caldenborgh, founder of Museum Voorlinden, praised his work for its ‘raving beauty, craftsmanship, and visual power that opens our eyes to the world of yesterday, today, and tomorrow.’ In 2023, Kueh was recognised as Young Designer at the Dutch Design Awards.

The winner of the NN Art Award 2025 will be announced on Friday 28 March at 20:00 in Kunsthal Rotterdam. During this celebratory evening, all exhibitions, including the NN Art Award exhibition, will be freely accessible to attending guests.

Written by Flor Linckens

In the DHB Art Space, made possible by new main partner DHB Bank, Rotterdam-based collective Unity in Diversity Rotterdam (UID) presents an interactive sound artwork by media artist Pedro Gil Farias (developed in collaboration with sound artist Marcin Sky). This artwork, Echoes of Us, focuses on a dreamed future for the residents of Zuid and the area development around Zuidplein and Rotterdam Ahoy. Following an ‘open call’, UID selected Rotterdam-based media artist Pedro Gil Farias from dozens of submissions. Echoes of Us gives a voice to the dreams of artists and residents in the neighbourhood, and invites visitors to Art Rotterdam to share their own dreams too. As an interactive tool, the artwork builds a collective dream for a liveable and sustainable future of Rotterdam South.

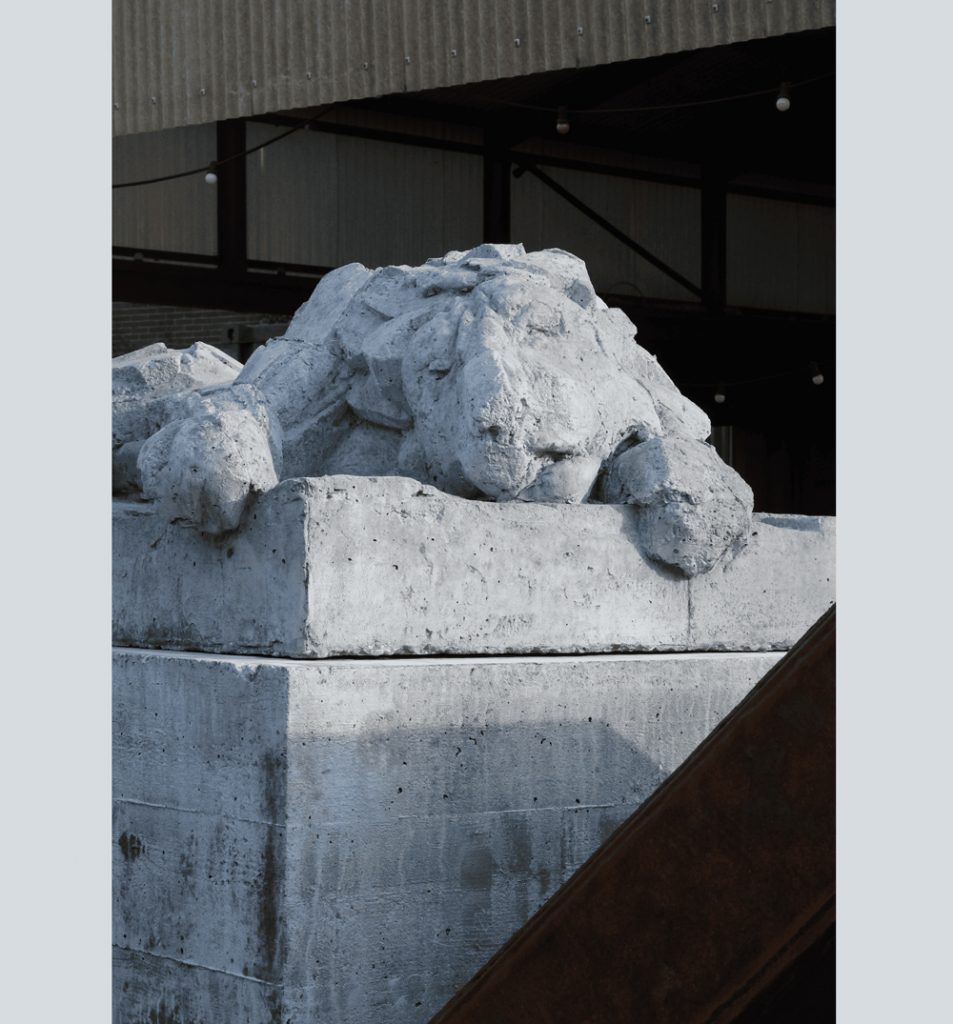

Atelier Van Lieshout (AVL) is known for monumental sculptures that merge art, architecture, and social research, balancing a playful yet confrontational tone. The work explores power, autonomy, and the role of the artist in a society where visibility and recognition are never guaranteed. Since 1995, Joep van Lieshout has worked under the name Atelier Van Lieshout, a deliberate choice to challenge the classical myth of the individual artist. At Art Rotterdam 2025, in collaboration with Galerie Ron Mandos, AVL presents the Tomb of the Unknown Artist (2024) in Sculpture Park, an homage to the many artists who have remained in the shadows of art history.

Tomb of the Unknown Artist: A Tragedy of Unrecognised Love

A concrete tomb rests on a gun carriage, the undercarriage of a cannon traditionally used to transport the coffins of generals, emperors, and heads of state to their final resting place. Once a symbol of state power and heroism, the gun carriage took on a ceremonial role in state funerals, marking national mourning on a grand scale. In many traditions, it is not a final resting place but merely a temporary means of transport to a grave or mausoleum. Here, it no longer carries a statesman but a monument to the forgotten artist. It is a symbolic transition between life and death, between oblivion and recognition.

Atop the tomb lies a bronze lion, still, perhaps asleep, perhaps lifeless. “That lion is a symbol of strength and perseverance,” says Joep van Lieshout. “The king of the animal kingdom sleeps, or dies, but could also wake up and move on.”

The work is both a monument and a commentary on the unpredictability of recognition. “Artists often lead incredibly tough lives,” says Van Lieshout. “I know so many people who dedicate their entire lives to creating beautiful things, only to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Some are later rediscovered; others disappear entirely. He calls it “a tragedy of unrecognised love.” The work carries a humorous undertone while being deeply serious at the same time. “Humour makes serious messages easier to digest,” he adds with a smile.

On the side of the sculpture, there is an opening, an alcove reminiscent of an ossuary, a place where human remains are stored. “We looked at ossuaries as a source of inspiration for this monument,” says Van Lieshout. “It is a sculpture that remains open to what is yet to come.” In the future, the bones and ashes of unknown artists could be placed here. It is not a closed monument but a space that can literally be filled with the physical remains of those who never received recognition.

Protected, Forgotten, Almighty?

Alongside the Tomb of the Unknown Artist, Atelier Van Lieshout presents three other sculptures at Art Rotterdam, each exploring, in its own way, the tension between protection, power, and erasure.

Tree of Life (2016) is a tree standing over three metres tall, bearing human-shaped fruit in various stages of ripeness. “It can be a representation of life and fertility, but just as much of violence and disappearance,” says Van Lieshout.

Maria’s Cloak (2023) questions who receives protection and who is left outside. Maria’s cloak does not offer automatic safety.

Omnipotent (2023) plays with authority and submission. “Omnipotent is another word for the Almighty,” says Van Lieshout. The sculpture depicts a hand whose meaning shifts depending on its positioning. “You can place it upright, and it becomes a stop sign. Turn it with the palm facing up, and suddenly, it becomes the begging hand of an artist.”

A Floral Tribute at the Monument

On 27 March 2025 at 19:00, a symbolic flower-laying ceremony will take place at the Tomb of the Unknown Artist (2024). Visitors are invited to bring flowers and lay them at the monument, a final tribute to the artists who remained invisible during their lifetimes. Joep van Lieshout will give a short speech about the work and its broader context within Art Rotterdam.

Is it a comic or tragic gesture? It seems to carry the same ambiguity as the lion resting atop the tomb.

Written by Emily Van Driessen

At Art Rotterdam (28-30 March at Rotterdam Ahoy), No Man’s Art Gallery presents a dual presentation featuring the work of Benjamin Francis and Tobias Thaens. For Francis, this marks the beginning of his collaboration with the gallery, which will continue with his solo exhibition ‘A foot between the door’, on view at the gallery in Amsterdam from 22 March until 20 April 2025.

In his multidisciplinary practice, Francis explores the hidden mechanisms of power, control and correction that shape our perception of right and wrong. Through installations, videos, sculptures, texts and performances, he exposes the underlying structures that define the individual. His work invites viewers to pause and consider: who makes the rules, and what happens when we rewrite them? Why do we seek control over our surroundings — both bodies and inanimate objects — and how does that lead to a rigid normativity and conformity?

Drawing inspiration from dance and the tension between obedience and resistance, Francis examines how subtle forms of correction — through language, body language or architecture — shape social structures and the human experience. In a society driven by efficiency, where deviation from the norm is deemed undesirable and imperfections are meticulously erased, his work creates space for doubt, discomfort and the imperfect. He investigates how errors and deviations are corrected or excluded within social, pedagogical and knowledge systems. This theme resonates with him personally: as someone with dyslexia, he experienced firsthand how spelling mistakes were treated as undesirable, subjecting him to constant correction. His work raises the question: who determines what is ‘right’, and what dogmas and power dynamics lie beneath? Does such a strict binary opposition between right and wrong even exist? Francis sees his art as a means not to conceal flaws and decay but to examine them, both in language and in material.

Language plays a central role in his research, and his work moves between object-based pieces and participatory performances, often placing the audience in unexpected situations and inviting them to become part of the installation. In a previous performance at Hotel Maria Kapel, where he completed a residency program, Francis used texts that had been repeatedly processed through translation software, revealing errors and misinterpretations. Participants were asked to read these texts aloud and relate to them, undermining the supposed objectivity and neutrality of language and exposing its entanglement with power and hierarchy. In these performances, the viewer is not merely an observer but an active participant in a constantly shifting system. In “A Claim for Your Own Good”, performed at the Luther Museum, Francis staged a fictional cleaning company that subtly exposed power dynamics through ritualised actions.

The relationship between body and memory also plays a crucial role. Our bodies make mistakes that shape our awareness. We feel things or are moved by them without always realising it. Memories are stored in our bodies, often without our conscious awareness.

A recurring motif in his work is the interplay between dirt and cleanliness. Excessive purification is bound to leaves traces. What remains is a reality that has been repeatedly polished, adjusted, corrected and purified. What does that do to a body that must constantly submit to this process, effectively becoming an archive of discipline? And how can we erase the traces of years of imposed correction, ingrained deep into our skin and minds? And what happens when cleaning is no longer just a physical act but a means of control? When purification is disguised as care — a care imposed upon you because, for whatever reason, you hold less power within the dominant system? Francis confronts the viewer with this paradoxical dynamic, where systems of power, correction and normativity are embedded in our most everyday actions.

The installations of the artist transform environments into performative spaces, making visitors acutely aware of their position within systems of discipline and normativity. A bathroom, a classroom, a mortuary, a ballet studio: functional spaces that he subtly disrupts, making them no longer ‘fit’. Their original function shifts, becomes unsettled, and gives way to tension and new meanings. In previous installations, such as “The Removal of the Eye” at P/////AKT, visitors were challenged to walk across fragile white tiles, each step leaving a mark: a direct confrontation with the tension between purity and decay, control and surrender. These fields of tension are central to his practice.

Francis continually returns to the notion of ‘the other’, those who deviate from the norm. It is a position that he identifies with personally as a queer person of colour with dyslexia. Those who do not fit into societal frameworks, for instance due to their social or economic position, are subject to greater control. By positioning ‘the other’ as the norm (the opposite of ‘othering’) he makes the norm itself visible, open to analysis and critique. He shifts the perspective: it is not ‘them’ who are questioned, but the norm itself. This process allows him to examine and challenge how these systems function and who enforces them. Authority and normativity are not fixed concepts but are constantly rewritten by the structures that uphold them.

At Art Rotterdam and in his solo exhibition at No Man’s Art Gallery, Francis explores the relationship between space and the body.

Benjamin Francis (1996) graduated from the Fine Arts department at ArtEZ BEAR in Arnhem in 2020, with a focus on Experiment, Art, and Research. His work has previously been shown at No Man’s Art Gallery, NL; Christine König Galerie, AU; Art Antwerp, BE; Luther Museum, NL; PuntWG, NL; Ballroom Project #6, BE; Hotel Maria Kapel, NL; If I Can’t Dance, Kunsthuis Syb, Het HEM, P/////AKT, NL; MÉLANGE, DE; Rencontres internationales, DE; SECONDroom, BE; and Mutter, NL.

At Art Rotterdam, Benjamin Francis will present his work in the booth of No Man’s Art Gallery. His solo exhibition will be on view at the gallery in Amsterdam from 22 March until 20 April 2025.

Written by Flor Linckens

On the way to his apartment one night, Jonas Brinker was walking through Times Square and much to his surprise, saw a dragonfly resting on the sidewalk in one of the busiest places in the world. Brinker had his camera with him and decided to kneel down and film the insect head-on. The dragonfly appears to be looking at us throughout the entire film because it is the only thing we see. But at the same time, we are able to take in much of the surroundings: the constantly changing lights of the LED billboards, sirens, cars and conversations.

“The work is centred on presence rather than meaning,” says Brinker. “The dragonfly is not there to represent anything, but to simply exist as an individual in that moment.” Untitled (25.07.2022, 02:14 AM) fits seamlessly with Brinker’s work, in which elements that have existed for a long time – the dragonfly has been around for around 320 million years – come together in a fleeting manner.

Jonas Brinker (Germany, 1989) is regarded as one of the most prominent video artists of his generation. His work has been exhibited at Marres in Maastricht (2018), Palais de Tokyo in Paris (2018), the Berlin nightclub Berghain (2020), and last year at Piccadilly Circus in London. We spoke with Jonas Brinker shortly before the opening of his first institutional solo exhibition at the Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof in Hamburg.

Jonas Brinker is presented by Zyrland Zoiropa, Berlin and his Untitled (25.07.2022, 02:14 AM) is on display in the Projections Section.

You mentioned earlier you were working on a major show at Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof in Hamburg last week. Are you pleased with how it turned out?

Yes, I was preparing my first institutional solo show at Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof in Hamburg. The exhibition revolves around fireflies in Central Park, translated into an expansive video installation within the historic waiting room of the Kunstverein. Their bioluminescent signals, emitted during their final phase of life for species-specific communication, are set against aerial shots of the New York skyline at night, transforming an attempt to capture their flashes into a melancholic exploration of longing, time and the interwoven worlds of human and non-human beings.

I’m really pleased with how the show turned out and just love the fact that the space is located between the tracks of a railway station, making it an especially compelling setting for time-based works.

The way your time-based works are presented is a key aspect of your work. What presentation did you have in mind/would be ideal for Untitled (25.07.2022, 02:14 AM)?

When I filmed the piece, I envisioned it being shown as a floor-standing projection, so the image extends into the actual space. The projection should be taller than a human, so we look at the insect at eye level or even slightly upward, creating an intimate situation where a small, easily overlooked being takes on a strong presence. The encounter gains weight, becoming something resonant.

At Art Rotterdam, Untitled (25.07.2022, 02:14 AM) will be featured in the Projections Section. It revolves around a dragonfly resting in New York’s Times Square. In it we see a close-up of the dragonfly, with its eyes and wings reflecting the changing lights in the surroundings. How did the idea of a dragonfly in Times Square come about?

Well, there’s an interesting connection here – it was not something I had planned or set out to film. I had been working on the other piece and while walking back to the apartment where I was staying downtown, I crossed Times Square in the middle of the night and spotted the dragonfly on the sidewalk. Since I had my camera with me, equipped with a macro lens, I decided to kneel down on the concrete and spend a moment filming the insect. So, in a way, the work is a direct response to an unlikely encounter, something that happened entirely by chance.

The dragonfly is all we see. You might describe it as a recording of the impressions of a dragonfly while resting in Times Square. Was that deliberate?

The deliberate choice here was to film the insect at eye level, with the camera aimed at it head-on. In turn, the dragonfly seems to be looking back at us. This makes it the subject of the encounter, a wild animal recognised as an individual, one I can see very clearly yet whose essence remains elusive. I was intrigued by the reflections of the city lights and billboards in its wings and eyes, in which the surroundings are both absorbed and refracted.

There’s also an element of deep time to it, the ancient insect, largely unchanged for 320 million years, resting on a sidewalk cast from concrete mixed with the glittering remnants of Manhattan’s bedrock, illuminated by the shifting colours of digital screens and advertisements. So, in many ways, I’m interested in what is already there – different elements coming together in a fleeting way.

Of course, we can only speculate on what the insect is observing, but the dragonfly was surely displaced, likely misled by the stark illumination of the square, causing it to get lost. After filming, I brought it to the nearest park.

Throughout history, animals are frequently used metaphorically: lions signify power, wolves represent freedom. The close-up in Untitled (25.07.2022, 02:14 AM) resists metaphorical interpretation. Why do you challenge anthropocentric narratives in your time-based works?

I’m interested in stepping away from the tendency to assign symbolic meaning to non-human animals. The dragonfly is not there to represent anything, but to simply exist as an individual in that moment. The work is centred on presence rather than meaning.

I try to keep that openness in my work, to perceive without imposing, to observe without assuming, to create space for an encounter in which meaning is not fixed but unfolding. By shifting the focus from interpretation to observation, I aim to acknowledge non-human subjectivity without reducing it to a human-assigned role. Even as I try to step away from anthropocentric narratives, I can only ever adopt a human perspective. But by being aware of this limitation, I hope to create a space in which meaning emerges through observation, rather than being imposed.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel

Artist Tanea Hynes grew up in Labrador City, a remote town in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, centred around one thing: iron ore mining. In her work, Hynes reflects on the impact of this industry on the people, nature and identity of the region. Through photography, drawings and installations, she explores how labour, nature and capitalism are intertwined.

Tanea Hynes’ work can be seen at the KIN booth in the New Art section.

A city built on iron

The name might be somewhat misleading, as Labrador City is not a city in the usual sense of the word. It is not a regional trade hub, it lacks a rich cultural life and young people do not move there for education. In Labrador City, everything revolves around mining, the starting point of a global production chain.

The town emerged in the 1960s after the discovery of a large iron ore deposit in the region. It was built according to the utopian ideals of the late 19th-century Garden City movement, intended to create a community where miners and their families could live well. For some time, those expectations were met. In its early years, the Iron Ore Company of Canada invested in modern facilities and social programmes, but after acquisitions by multinationals like Rio Tinto and Mitsubishi, these amenities disappeared.

These social programmes were not a luxury, given that the surrounding area consists of nothing but forest and wilderness. If someone were to go missing in the woods, finding them would be like searching for a needle in a haystack, Hynes notes in her graduation project. The nearest major city, Montreal, is 1,250 km away as the crow flies—roughly the distance from Rotterdam to northern Spain. The population currently fluctuates around 7,500. At its peak in the mid-1970s, the town had 12,000 residents.

These population fluctuations are linked to the global demand for iron ore. Born in 1996, Tanea Hynes has witnessed multiple boom-and-bust cycles over the past decades. Periods of economic prosperity have alternated with deep recessions, during which people lost their jobs, mortgages went unpaid and houses became unsellable. These cycles leave not only an economic imprint, but also shape the social fabric of the town. Labrador City has its own class system of miners and management, each with its own interests, often clashing over labour conditions and wages.

The mine as lifeline and curse

Hynes’ own life is inextricably linked to mining. To finance her studies, she spent five summers working as a truck driver in an open-pit mine. She experienced firsthand the physical and mental toll of the work and relentless pressure to increase production. The mines operate 24/7, 365 days a year, and work only stops in the event of serious accidents.

Reflecting on this experience, Hynes writes:

“This experience helped to shape my perspective on global economics, natural resource extraction, human impact on ecological systems, labor politics, and the world at large. I hold an understanding of the unforgiving demands of the mining industry and the place of myself, my family, and my closest friends within that system. I have experienced many close calls and felt the pressures of the endless push for faster production. Furthermore, I have felt my own body resist in ways that I cannot put into words. These experiences fuel my desire to create urgent works of art and photographs, attempts to materialize what can only be felt in one’s gut.”

This relentless pace impacts not only the workers, but also the landscape. Hynes’ work focuses on both. In theoretical discussions, mining is often—and rightly—equated with environmental destruction. But for those embedded in such a community, like Hynes, mining is more than just devastation. Alongside boredom, addiction and physical pain, there is also hope, solidarity and resilience. She highlights people who care about the natural world and rely on it for physical and mental well-being, relaxation and joy. Her images capture miners spending their free time in nature, seeking peace in the same ecosystem they extract resources from during the week. The relationship between miners, the mine and nature is therefore highly complex.

Testimony and protest

Hynes’ work is often compared to the documentary tradition of Newfoundland and Labrador. In the 1950s–1970s, documentaries played a key role in exposing social inequality and the consequences of large-scale mining. Since then, the mining industry has preferred to stay out of the media, keeping its gates closed to outsiders.

In the fall of 2023, a childhood friend—now in a management position—invited Hynes to photograph a mine. She was surprised at how casually the offer was made. Her upbringing in Labrador City and her connection to the community likely played a role, making her an insider. It may also relate to her less overtly activist approach compared to past documentary filmmakers. Hynes acknowledges the paradox of mining: it is destructive, yet it provides her community’s livelihood.

This paradox is evident in her description of the images she captured in the mine: “While this industry provides vital metals to the ever-expanding world at large, these scenes represent the epicenter of so much chaos, of pain, addiction, sadness, and bleak degradation.” She recognises the importance of mining, yet the cost is undeniably high.

Remediated

In her series Remediated, Hynes juxtaposes images of the mine with pictures of abandoned landscapes where nature is attempting to recover. Sites that were once bustling workplaces are now scars on the land. She poses a crucial question: What remains when the resources are depleted and the mines are abandoned?

Long-term damage from mining is often shifted onto local communities like Labrador City. This series is not on display at Art Rotterdam, but does it gives us an idea why Hynes remains hopeful: “Remediated, along with the portraits in my exhibition, communicate that there is a path forward, and that we are already on that path. The way forward is not only through physical remediation of the land, but in meaningful, mutually beneficial communion with both the land and with each other.”

The road ahead

For Hynes, the way forward lies in an Indigenous, anti-colonial perspective—one that does not consider the earth a collection of extractable commodities, but as an extension of ourselves. In this view, the earth nurtures us and embodies languages, stories and histories.

The broader theme underlying Hynes’ work is humanity’s relationship with the land. Mining occurs worldwide—Labrador City is only one example. The scale surpasses the individual and likely even our imagination. Millions of tons of rock are moved, rivers rerouted and mountains erased. The miners of Labrador City are merely one link in a vast system. They never see the end products of their labour, as the extracted materials are processed elsewhere.

Hynes’ work is both a stark reminder that every industry carries a human and ecological cost and a plea for a new way of thinking about land use. Rather than viewing the earth as an endless source of economic gain, we should see it as an extension of ourselves, a place that deserves care and respect.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel

“Art Rotterdam will be a total experience,” says fair director Fons Hof about the first edition of the fair at Ahoy. Naturally, this includes a culinary experience. Café Marseille, a well-known name in Rotterdam, is bringing the charm of southern French cuisine to the event. We spoke with chef Derk Jan Wooldrik about the restaurant & apéro bar that will be opening its doors during Art Rotterdam.

“We are a cheeky, slightly sexy restaurant with a multicultural menu,” says Derk Jan Wooldrik, describing his restaurant. Wooldrik began his career as a ship’s cook, sailing around the world for several years before working on land. He is now co-owner of the Rotterdam restaurant Café Marseille. Together with Kristian de Leeuw, he also owns the Double Trouble Hospitality Group, which includes Bar Bilbao, Bar Alaska and Eurobrouwers. Wooldrik and De Leeuw wanted to transform the atmosphere of their restaurant on Kruiskade into a pop-up version at the fair.

They enlisted set designer and decorator Ben Zuydwijk to create the design. Zuydwijk made his name in the film industry and has won two Golden Calf awards, the latest for Hardcore Never Dies (2023). “We worked with him in the past on a Basque pop-up restaurant at Station Bergweg, where he designed a Basque punk bar called Bar Bilbao. He has a unique perspective and is a fast thinker,” says Wooldrik.

A set designer creating a restaurant may not be the most obvious choice, but considering Wooldrik’s cookbook, it makes sense. Both think in terms of experience, atmosphere and storytelling. In the foreword, Wooldrik describes himself as a rudderless ship’s cook, an adventurer without a compass. “We are storytellers. We feel at home at life’s crossroads, where trade thrives, nationalities clash and collaborate, different languages are spoken and all kinds of scents and flavours come together in a feast for the soul.” He paints a picture of these places in vivid detail: “We are in the dark alleyways of Marseille, the smoky bars of Mumbai, the sweltering streets of Havana and the docks of Rotterdam.”

Wooldrik’s dishes are based partly on memories of the port cities where he once set foot and the food he ate there. Like in Palermo, Havana and Marseille, they are created with the everyday ingredients that are available: onions, tubers, turnips, whiting and bycatch. He prefers to use no more than three or four ingredients in each dish. At the heart of every dish are Wooldrik’s famous sauces, condiments and spice blends. At Art Rotterdam, Café Marseille will be serving bouillabaisse (fish soup), braised beef chuck, sardines and lobster, among other dishes.

Opening hours | Reservations not possible

| Thursday March 27(opening day, invitees only) | 11.00 – 21:00 hrs |

| Friday March 28 – Sunday March 30 | 11.00 – 19:00 hrs |

Also available at the pop-up restaurant: Café Marseille: Harbor Cookbook, Het havenkookboek van een stuurloze scheepskok (The harbor cookbook of a rudderless ship’s cook). This is not a cookbook as you know it. Alongside Wooldrik’s best dishes, it is a chronicle of his cooking adventures as a ship’s cook, a journey through eight port cities where he continually lost—and found—himself in a maze of ingredients, scents and memories.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel