Coming soon

Coming soon

Select type

During Art Rotterdam you will see the work of hundreds of artists from all over the world. In this series, we highlight a number of artists who will show remarkable work during the fair.

Moshekwa Langa was born in 1975 in the village of Bakenberg in South Africa, during the period of apartheid. Before he focused on the visual arts, he worked for the South African Broadcasting Corporation for a while. He also started experimenting with text, sculpture and sound recordings. In 1997 he was invited for a residency program at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. Since then, the Dutch capital has been an important base for the artist. Later on, he completed residencies at the Thami Mnyele Foundation in Amsterdam and the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris.

But it is his native village of Bakenberg that has always played an important role in his imagination. He returns there regularly and made his video work “Where do I begin” (2001) there, which was shown at the Venice Biennale in 2003, in Fondation Louis Vuitton in 2017 and until recently [early December 2022] in a retrospective at KM21 in The Hague. The artist’s key work is also part of the Tate Modern collection. The title refers to the song Love Story by Shirley Bassey. Langa only uses a snippet from the song and repeats it throughout the video. For four minutes we see people boarding a bus on a dusty road in Bakenberg, seen from the perspective of a small child. Langa deprives us of a narrative, we only see a series of anonymous legs. Yet the images provide visual information: perfectly ironed trousers next to worn-out shoes, a flowery skirt, an umbrella, an overflowing bag, stained clothing, a missing sock. The sentence “Where do I begin” suggests the beginning of a journey or a story. In combination with the repetitive movement, it says something about themes that recur frequently in Langa’s practice: travel, belonging, displacement, memories, identity, inclusion and exclusion, displacement and borders.

At the same time, the video implicitly speaks about the history of South Africa. During the apartheid regime, the National Party had allocated certain areas to black residents, the so-called homelands. That meant that many black residents had to travel great distances every day on their way to work. Bakenberg was not mentioned on any official maps during apartheid, a fact that thoroughly confused the artist when he first found out. It is therefore no coincidence that fictional and incomplete maps play a recurring role in his work. In a way, Bakenberg remains a static memory for Langa, yet he also reflects on contemporary developments in his native village, for example due to the rise of local platinum mining.

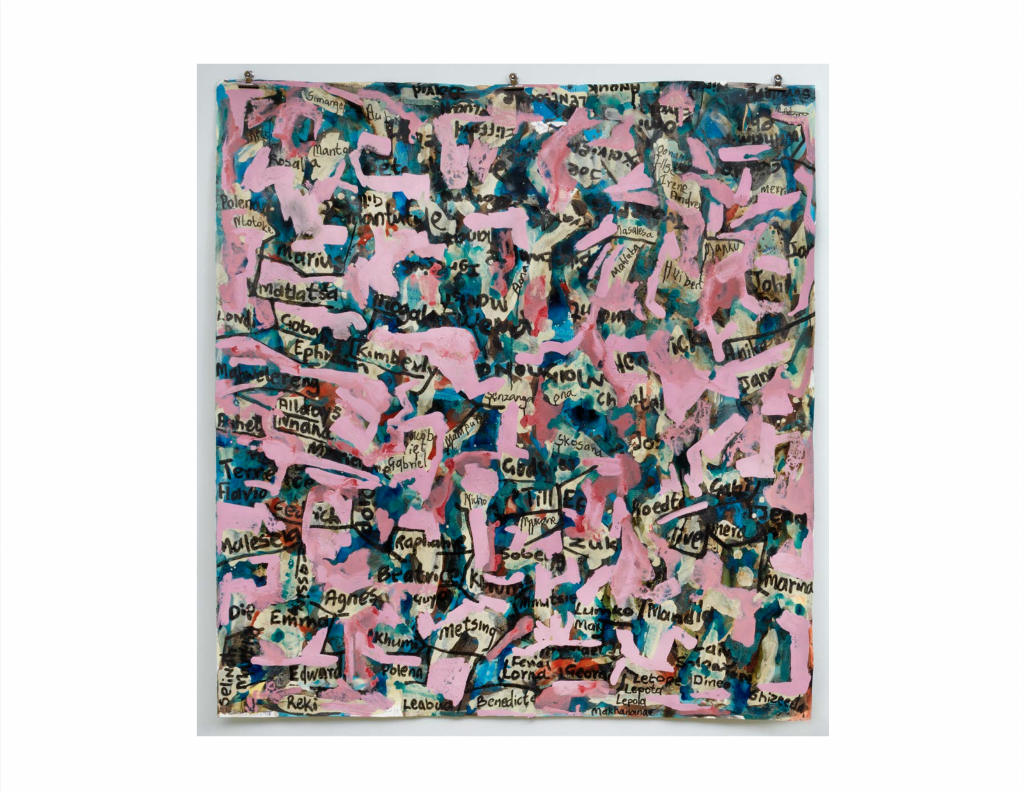

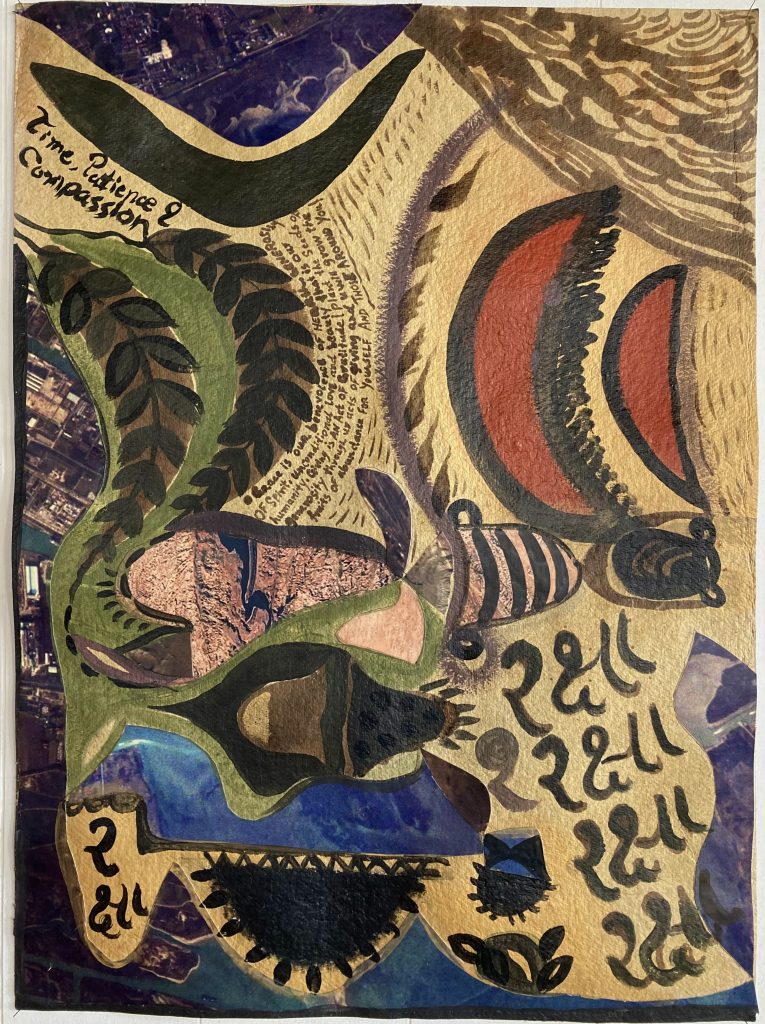

Langa’s practice is about living between different places, both in a physical and mental sense. He works in a multitude of media: from drawing and photography to video, collage and installation. The artist likes to experiment with different materials and uses salt, coffee, bills, paint, bubble wrap, pigments, cigarette butts, tape, Vaseline, cards, bleach, advertisements, corrugated iron, lacquer, plastic and natural charcoal. Language is also a regular feature in his practice. The artist also made a series of drag paintings that he dragged over the unpaved roads of Bakenberg to create a kind of abstract map of the area. Langa’s mostly abstract works are not infrequently marked by a thick texture: the artist layers the materials in the same way he layers meanings — which, incidentally, are not always easy to decipher. The titles of the works often resemble a riddle. Langa regularly applies the paint in puddles and will leave room for chance and free association. The viewer is also invited to associate freely.

Langa’s work has been part of the Biennials of Venice, São Paulo, Johannesburg, Berlin, Havana, Gwangju and Istanbul and has been included in the collections of MoMA in New York, M HKA in Antwerp and Tate Modern in London. Furthermore, Langa presented his work at Fondation Louis Vuitton and Fondation Kadist in Paris, the MAXXI (Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo) in Rome, the New Museum and the International Center of Photography in New York, Center d’Art Contemporain in Geneva, Kunsthalle Bern, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the ZKM Museum of Contemporary Art in Karlsruhe and Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam.

During Art Rotterdam, Moshekwa Langa will show his work in the booth of Stevenson in the Main Section.

Written by Flor Linckens

During Art Rotterdam you will see the work of hundreds of artists from all over the world. In this series we highlight a number of artists who will show remarkable work during the fair.

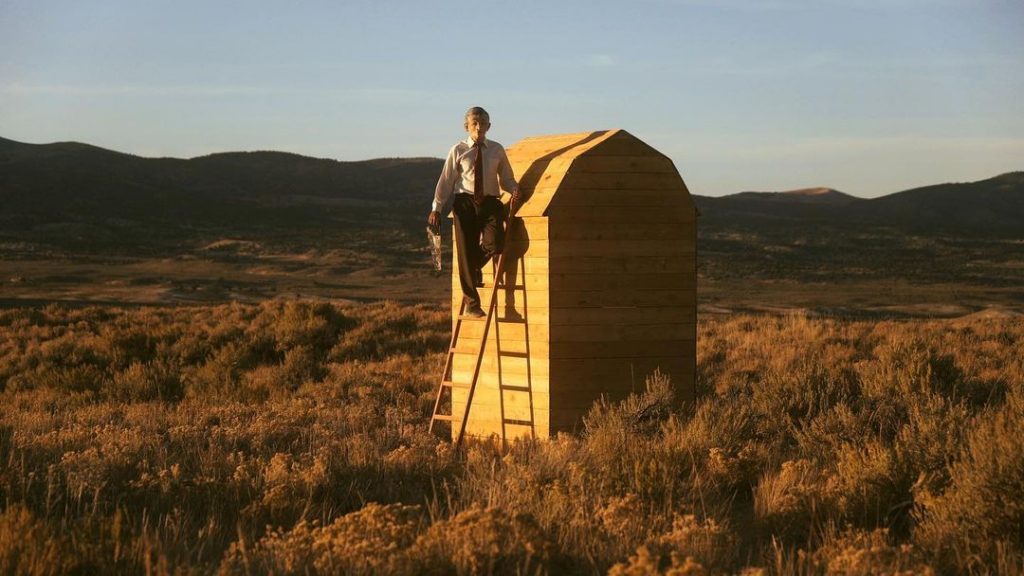

The German conceptual artist Erik Niedling is a bit of an enigma. He previously burned some of his earlier work and thinks about ways to fake his own disappearance. His works are about the ways in which we shape history and what that means for how that same history is collectively remembered. How do we collect, archive and organize things and what does that say about how we look at the world?

In 2010, Niedling co-directed and produced the documentary The Future of Art with Ingo Niermann, in which they interviewed leading curators, collectors, artists and art critics from the contemporary art scene, including Damien Hirst, Marina Abramović, Olafur Eliasson and Hans-Ulrich Obrist. A year later, the documentary was accompanied by a transcript in the book The Future of Art: A Manual. In it, Niermann proposes the idea of a special contemporary pyramid as a monumental work of art. Ideally, it would be financed by a single collector, who would then ensure a unique burial place after their death. In this line of thinking, the collector becomes a modern pharaoh, while indirectly elevating the artist as well. The project should be viewed through the lens of irony and sarcasm; it says something about the absurd amount of money flowing through the art market and the somewhat curious veneration for its players. In the documentary, Niermann and Niedling ask the curators, collectors, artists and art critics for advice to make the project an artistic and financial success. Their answers are sometimes a bit megalomaniac (Hirst) or self-aggrandizing (collector Thomas Olbricht) and few of the interviewees really criticize the rather absurdist plan.

At the end of the recording, Niermann hands over the idea to Niedling, for whom it has been the basis of many of his art projects ever since. One such project, “Mein letztes Jahr” (“My last year”) (2011-2012), involved him living for a year as if it were his last. He burned his earthly possessions and previous works and used the ashes to create new works. He captured the period in the work The Future of Art: A Diary, a sequel to The Future of Art: A Manual. He later made performances, publications and exhibitions about the pyramid mountain, for which he researched radical political movements in the state of Thuringia, among other things. He founded the Dokumentationszentrum Thüringen for this purpose, together with Niermann. On 8 May 8 2017, Niedling performed a ritual seizure of the Kleiner Gleichberg — on the day the Nazis surrendered to the Allies, 72 years before.

Niedling’s official statement was as follows:“I would like to build the largest tomb of all time and be buried there after my death, along with my artwork. Conceived by writer Ingo Niermann as part of our documentation The Future of Art (2010), Pyramid Mountain is a pyramid excavated from a mountain, standing no less than 200 meters high. Once I am buried, the carved-away material will once again be poured over the pyramid, effectively restoring the mountain to its original form. For the past seven years, I have been trying to create the necessary conditions to stage my own disappearance in a monumental way. I lived for one year as though it were my last, tried my hand as a political adviser and initiator of a new fitness movement to obtain the necessary financial resources, and created a new currency, the Pyramid Dollar. In 2012, I declared the Kleiner Gleichberg in my home state of Thuringia the future site of Pyramid Mountain, opening what amounted to a broad front of resistance. The multi-year international search for an alternative mountain proved unsuccessful, and I once again turned my attention to Kleiner Gleichberg: a highly visible landmark and natural bulwark used by everyone from the Celts to the East German National People’s Army. At 12 pm on May 8, 2017, I seized the Kleiner Gleichberg in an act of civil disobedience until final completion of Pyramid Mountain. As a sign of my claim, I will fix a flag on the summit, erect a pile of rocks in the shape of a pyramid and install a permanent exhibition with future grave items there. In a world where Donald Trump can become President of the United States, anything is possible: I am taking advantage of this propitious, revolutionary moment to set new rules. I have understood that only they who are ready for confrontation achieve their goal.”

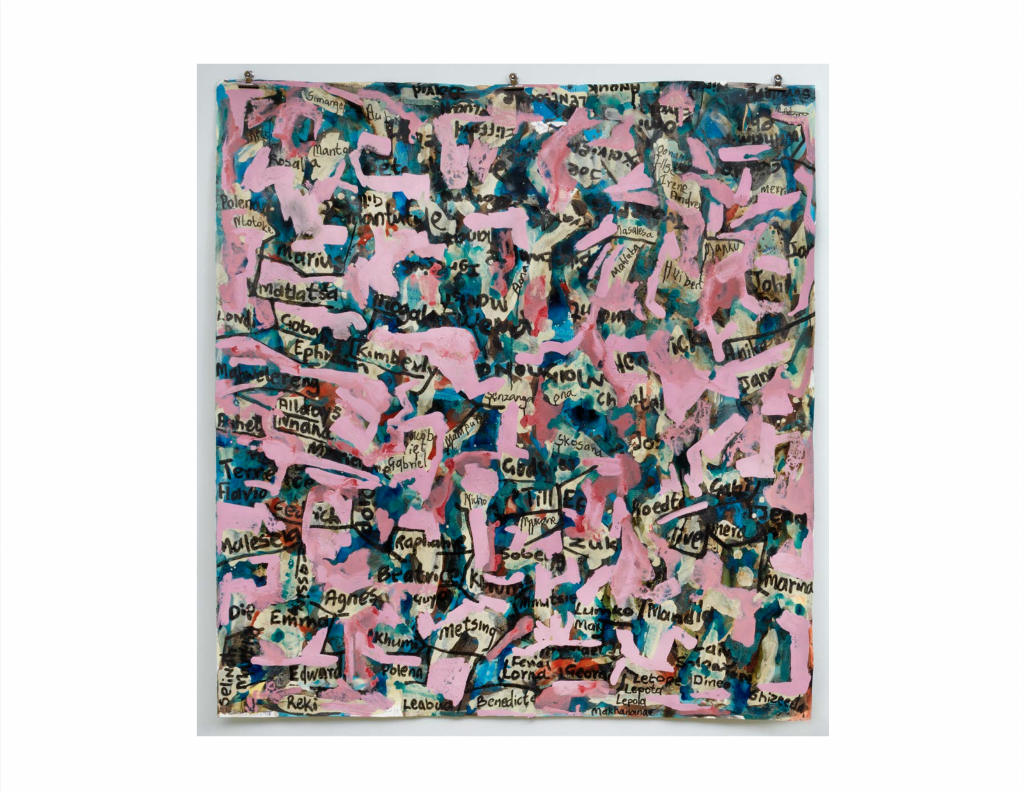

Since then, Niedling has performed “Burial of the White Man” on the mountain on the same day each year, symbolically burying the archetype of the white man, historically a symbol of oppression and violence. In 2019, he released an eponymous book, a biographical novel about his friendship with Niermann and the execution of a series of projects in extension of the pyramid that become increasingly large, absurd and ambitious — all of which seem, in essence, doomed to fail.

During Art Rotterdam, Erik Niedling will show his work in the booth of Galerie Tobias Naehring in the New Art Section. In it, the project of the pyramid mountain takes shape in a series of photographs, paintings and other works of art. Niedling’s work has previously been shown at Manifesta 12, the M HKA museum, De Appel Arts Centre, the Neues Museum Weimar and the Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst GfZK.

Written by Flor Linckens

During Art Rotterdam you will see the work of hundreds of artists from all over the world. In this series we highlight a number of artists who will show remarkable work during the fair.

When De Volkskrant newspaper reported on Art Rotterdam in 2021, the headline was clear: ‘Artist Iriée Zamblé stands out at Art Rotterdam’. Zamblé (1995) immediately attracted attention after graduating from the HKU in 2019. She was offered a studio in The Rembrandt House Museum, a residency at Roodkapje Rotterdam and she won several awards, including the Sprouts Young Talents Award and the Royal [Dutch] Award for Modern Painting. One of her murals is currently on display in Stedelijk Museum Schiedam and her work has been included in the collections of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ahold and The Rembrandt House Museum, among others.

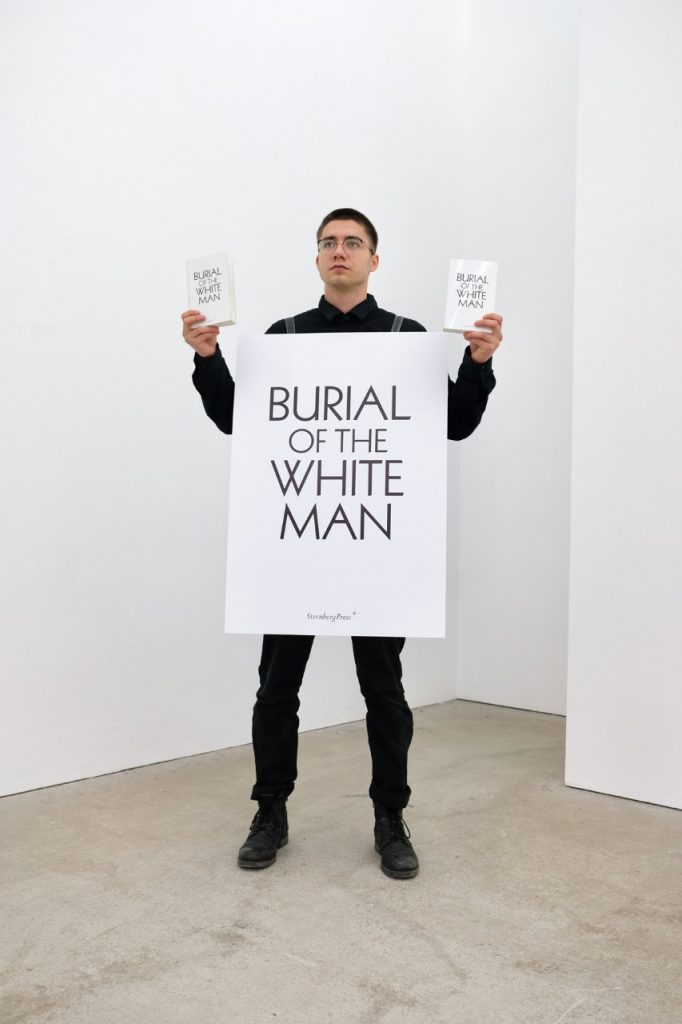

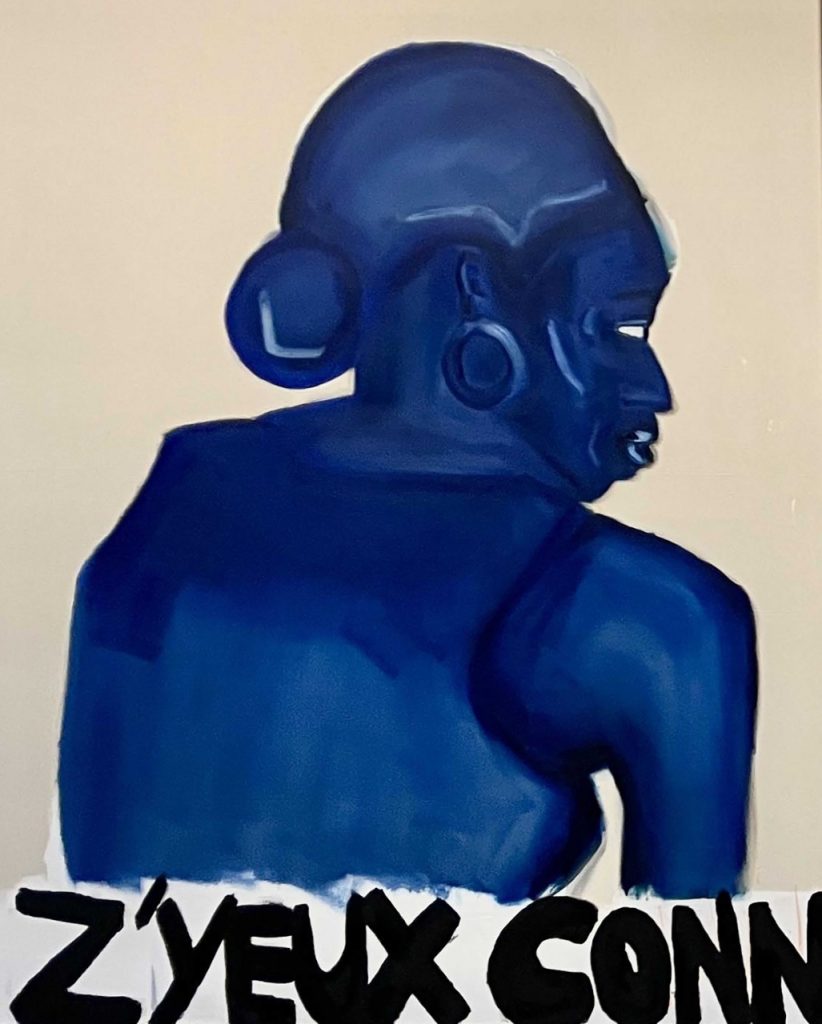

Zamblé is known for her expressive portraits on paper and canvas in which black people play a leading role, while they are usually the exception in the art historical canon. Where a painter like Kehinde Wiley often places the black body in elevated positions — like a contemporary Napoleon on horseback — Zamblé does the opposite: she shows everyday black people you might encounter on the street. She is inspired by photos of passers-by and appropriates certain elements of their appearance or clothing and then creates a new character on the canvas. Their personality emerges powerfully in those paintings. She works quickly, in rough lines, with materials such as acrylic, oil paint, pastel and spray paint. Zamblé is also intrigued by West African studio photography by artists like Sanlé Sory, who used striking fabrics for his backgrounds.

The artist is looking for a certain coolness, as defined in West Africa and African diaspora cultures. Her characters are empowered and have agency over their lives and decisions. They are confident and proud in their language, dress and attitude and dare to take up space. In the West, this coolness is almost an act of defiance against a history of oppression and a contemporary society in which white people and systemic racism are still the norm. These people reclaim and redefine blackness in a new context, stripped of colonial connotations. For example, Amsterdam-based artist Tyna Adebowale once said, “Before travelling outside Nigeria I never saw myself as black.” In her practice, Zamblé offer a critical look at the white lens as an automatic frame of reference, but also, for example, at the (short-term) performative activism after the Black Lives Matter protests. She is looking for more sustainable and effective ways to keep the conversation going about these topics. Zamblé is idealistic and hopes to make us look at the world in a new way, but at the same time she hopes that we will mainly see humanity in her work and not just blackness. That it evokes a certain curiosity about the person depicted.

Opposite to that coolness is a desire for self-protection. Where some characters stand confidently in the picture, others lower their eyes or hide behind hoodies. In addition, the artist is also interested in care, a theme within feminist theory that is increasingly reflected in the art world — not surprising as a counter-movement in a world (and discourse) in which struggle and activism play an significant role. Zamblé’s practice is also marked by fun; her booth at Art Rotterdam in 2021 was a total experience and was rarely empty. In addition to works of art, she also paints bags and produces merchandise, because she believes that her work should be accessible to everyone.

Zamblé is also inspired by the work of Ralph Ellison from the 1950s, who wrote about his experiences as a black American and the social problems and political and intellectual movements within that context. The book Afropean by the British writer, photographer and presenter Johny Pitts also plays a role in Zamblé’s practice. For this book, Pitts traveled through pre-Brexit Europe — from Lisbon and Paris to Stockholm — and spoke to several Europeans with African roots. For Pitts, the more equal term Afropean offered an opportunity to look at his own identity in a new way, not as half European and half “different”, as half “deviating from the white norm”, but rather as one unified term that doesn’t pit two sides of his identity against each other.

Zamblé’s practice is theoretically layered, but her paintings are in essence also accessible to people outside of the art world. Her latest works, that will be shown at Art Rotterdam, take a closer look at language, as a means of self-ownership (to include and exclude people). Zamblé: “I want to draw a new line in the legibility of my paintings. I think it’s interesting to see who you speak to as an artist and which language dominates in a space.”

During Art Rotterdam you can view Zamblé’s work in the Prospects exhibition of the Mondriaan Fund. For the 11th time in a row, the Mondriaan Fund presents the work of starting artists here. All 73 artists who show their work this year will receive a financial contribution from the Mondriaan Fund in 2021 to start their career.

Written by Flor Linckens

Laura Jatkowski shows Unvergessen at Prospects, an installation for which she worked removed tombstones with a drill. With this relatively simple intervention, the German artist touches on major themes such as life, death, mortality and the importance of objects such as tombstones as carriers of memories. It earned Jatkowski a nomination for the NN Art Award.

Laura Jatkowski (Germany, 1990) was trained as a sculptor in Glasgow and completed a Master’s degree at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. After her studies, she was involved in the establishment of the Trixie studio complex-cum-project space in The Hague. She lives and works in The Hague and Berlin.

At Prospects you will be showing Unvergessen, a body of work consisting of discarded gravestones. When you first discovered them at Berlin’s Zionsfriedhof were you immediately aware of their potential? `

I wouldn’t say I saw potential, but the moment I discovered the pile, it left an impression on me, and I couldn’t get the image out of my head. We are speaking of at least 100 stones roughly thrown on top of one another. Depending on the culture, but in many European countries, it is common that one does not own a gravesite; instead, one leases it for ten up to twenty years. If the contract is not extended, these stones will be removed from the grave and demolished.

You’ve drilled out the letters of the headstones. How did you decide on that?

The idea to extract the letters evolved while thinking about the object and how to approach it. A headstone is a personal object that holds value and memories that do not belong directly to me. The object’s purpose of preserving memory is no longer given once they are removed from the grave to be erased. The gesture of extracting the letters allowed me to highlight the sense of erasure while at the same time bringing them back to people’s attention. My original starting point was to use the letters only and reassemble them into words/sentences. In the making, I realized the letters were already charged with so much meaning that this gesture felt forced. Later, while seeing the empty negatives of the grave markers, I realized that they indeed hold potential that I hadn’t realized before, so I decided to incorporate them into my installation.

What is Unvergessen about? Could you tell us a little bit about the themes you are addressing?

The work addresses loss and death and confronts the viewer with mortality. With this work, I am interested in exploring how memory is a valuable resource and how it is not only embedded within narratives but also in material artefacts and objects. The processes of remembering and forgetting and how memories are linked to objects make me curious. Memory is a strange process. It is with you every day and informs who you are. I am always surprised how some people can remember the smallest details where I tend to forget. There is an urge to remember and to be remembered. Humans have always created objects to hold their memories; we collect and accumulate things around us to keep us remembering and to counteract oblivion. I do not see forgetting as only negative. It also can allow one to reinvent themselves and move on, and sometimes it’s necessary to forget. How do we treat these memory objects and spaces? How do we preserve memories and keep them alive?

In previous works you’ve touched on topics such as mending flat tires and the contents of someone’s fridge as a way describing someone’s personality and desires. How does this project fit in with your previous work?

This project continues one of the central questions I engage within my practice: how particular objects and gestures carry emotional values and histories. I often work with everyday materials and take them out of their original context placing them in a new system of relationships.

Everyday objects or gestures offer an immediate connection for the viewer—there is already a relationship between the object and the person, a certain kind of ‘pre-history’ that is already embedded within their traces. This ‘pre-history’ carries information and signifiers. In this way, I can recharge the materials by showing them in a context unfamiliar to the viewer. For me, finding a suitable form that creates a level of abstraction is important. Between the concrete and the abstract, a space of tension is created and suddenly, a new space opens up that the viewer can fill with their questions and imagination.

In terms of tembre I can definitely tell there’s a sense of humour and playfulness to the excellent fridge door installation, but Unvergessen seems to strike a more serious tone. Do you agree to that statement and did you intend to make something of that nature, something emotional yet cerebral?

For me thinking and feeling are not separated from one another. It is indeed true that my works have different atmospheres. As I work mainly with everyday objects, each one brings their own connotations and references. My work puts to question our relationship with the given object. Some everyday objects like the fridge door or a wheelbarrow give me more room to approach and play with them during the process of creation, whereas with these headstones, due to the context of the object, I felt my room for intervention is limited.

Before attending the KABK, you’ve obtained a BA in Sculpture in Glasgow. Do you consider yourself a sculptor or an artist not bound to a specific discipline?

I started my BA in Glasgow and finished it in the Netherlands. Even though I have a background in sculpture, I do not tie myself to any medium. With every idea, I experiment and see which medium is best to carry it. The result can then be a video, an installation or a sculpture. Nevertheless, the discipline of sculpture and has informed my thinking a lot. So, when it comes to installing a work, I think like a sculptor. The placement in relation to the viewer’s body, how it makes them perceive and move through space is important to me.

You’re one of the founding members of Trixie, the Hague’s studio complex annex artist-run art space. How did this initiative come about and why did you decide to get involved?

After graduation, I faced the challenge of finding myself without a studio like most art graduates. The academy to which I would usually go and do work while having a coffee with my friends and talking about art was gone. Shortly after, I found a studio, but the community was missing, like a car without fuel; both are crucial for me. Therefore, I gathered some artists, and we looked for options to create that for ourselves. With Stroom Den Haag‘s generous help, we found a space within The Hague city centre in 2018. Trixie has a gallery space, 15 studios and a big kitchen to cook and talk. Since it began, Trixie has become a well-known space within the cultural scene in The Hague and has allowed me to meet many great artists, form friendships and learn from each of them.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel

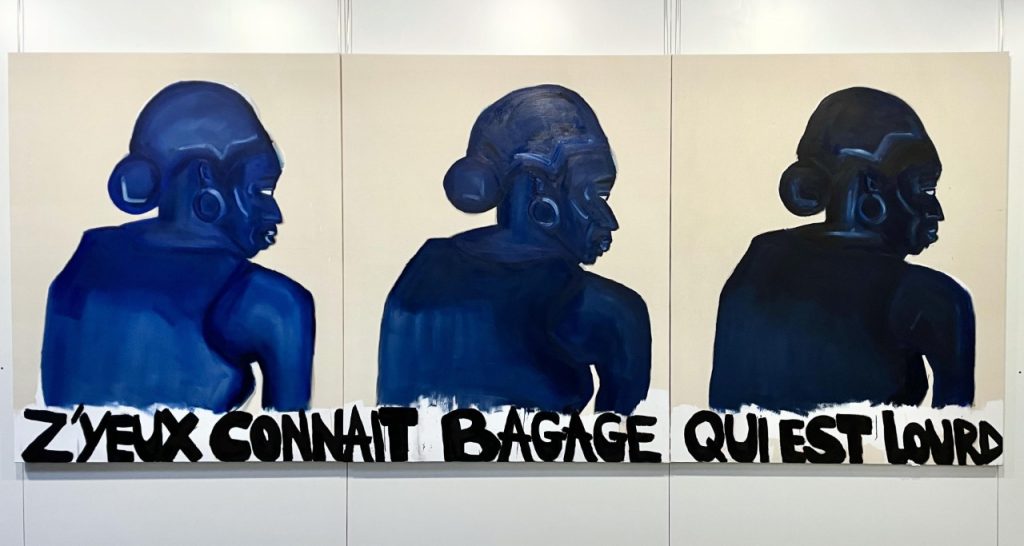

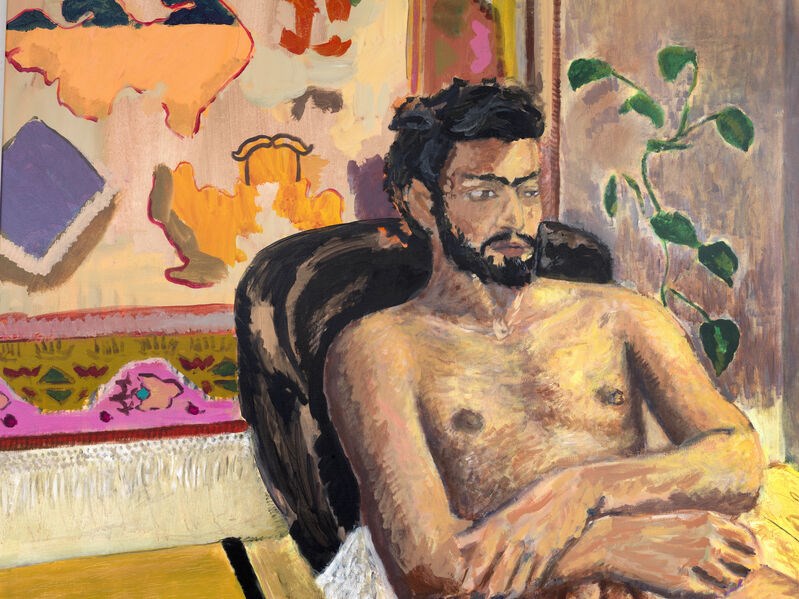

In the Solo/Duo Section, No Man’s Art Gallery shows new work by painter Sam Samiee. In his work, Samiee combines a Western visual language with Eastern narratives and psychoanalytic concepts. Samiee is always looking for shared traditions. He previously found it in abstract work. This time, he focusses on Nastaliq calligraphy. A conversation about the importance of 1001 Nights, transnationalism, Freud’s ideas about framing and the Dutch René Daniëls.

Sam Samiee was born in Tehran (Iran, 1988). He completed his residency at the Rijksakademie in 2015 and completed ArtEZ AKI in 2013. Prior to that, Samiee studied industrial design and painting at the University of Arts in Tehran. Samiee won the Dutch Royal Prize for Painting in 2016 and the Wolvecam Prize in 2018. He is currently a member of the jury for both prizes. Samiee’s work is shown internationally and was shown earlier this year at Melly in Rotterdam.

What will you be showing at Art Rotterdam?

I assume that I will be showing a new work from the series that I’m working on called Nastaliq. Nastaliq is a type of calligraphy which is used mostly in Persian and Urdu. And so in the Eastern Islamic art, not in Western Islamic art, which is more geometrical. The Eastern Islamic world, which includes North India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Kurdistan, tends to use Nastaliq. This is what I’m trying to focus on, on the beauty and representation of groups of people who I don’t want to bind them to nation states, to the concept of Iran or Afghanistan.

I would like to signify this group of people with a type of aesthetic that they relate to transnationally. That’s why I call it Nastaliq. In the portrait it might be an Indian boy or an Afghan boy or an or a Kurdish girl or an Armenian boy.

So the series takes its name from eastern Islamic calligraphy, yet the canvasses are painted in a Western style. Why is that?

My education is Western art and in visual arts. So, usually my references are very heavily about Western art history for this series. For the last two to three years, I’m particularly looking at Bonnard more than anybody else, because of his position in European history; postwar, prewar, postwar. As Bonnard, and Matisse too, was an artist who would go unapologetically for decoration. There are also other references to cinematographers and theorists like Pasolini. I think these artists are also looking for a shared tradition that I would say is very related to 1001 nights. I am talking about the usage of aesthetics for the sake of ethics.

You mentioned 1001 Nights and the concept of transnationalism, how are these concepts related and why are they central to your work?

I try to work very discursively based on art history, modes of work. I think in European art history we have well researched intertwined networks of empire and nation states. But when it gets to the intertwined networks of Asia or West Asia, there’s very little scholarship in Europe on art, historical understanding of references or literature of the intertwined networks of Asia, of West Asia.

So I wouldn’t like to concentrate too much on Iran, because not only Iran that has these traditions, it’s Indo Iranian. It has a lot of Arabic influences, Ottoman influences, Turkish influences, and North African influences too. So, when 1001 nights was translated into Latin in 17th century and then into French and English and other languages it became, as Jorge Luis Borges wrote, transnational. It’s not really Persian, it’s not really Arabic. It’s a shared tradition. I’m very interested in taking something out of the realm of identity politics of one particular group of people. That’s why I insist on transnationalism.

Is this also the reason you are interested in abstractionism, because it transcends national or local identities?

Yes, that is correct.

I recently saw your show at Melly in which you tried to escape the traditional frame of a canvas. Why is that important to you?

I’ve been doing this since 2014-15, when I was at the Rijksakademie. I am addressing the very fundamental question of how to deconstruct painting. Again, it was very related to 1001 nights, because 1001 nights is not just a set of stories. It’s a programme for framing. How can you produce a frame of a story? Then from within that frame, you enter another frame, and then from that frame you enter another frame. By breaking frames over and over, you also influence the modes of relation within the frame that you are in together with the person who is hearing the story.

This is very similar to the psychoanalytic idea of the frame, because in psychoanalysis Freud produces a mode of relation to the patient, which is not so much about the content of what the patient says, but more about when the patient should come in, when he would lie on the couch, when they finish, what should be the exchange between the analyst and the patient. So the framework as the mode of relationality.

How do you apply these concepts to painting?

I arrived at this question from two ways. One, after the 1970’s, you rarely see painting commenting on architecture. Expect in Europe, except in the work of Constant Nieuwenhuis and COBRA artist. They were situationists. The situation is very much about the architecture, but also about mode of relation, mode of production: who is there, who is playing, who is not playing, who is excluded, who is included. So all these questions relate to the framework.

And through Paul Thek. I think Thek was a great example of a person in seventies and eighties who broke away from the frame of the painting and thought about the painting again within the architecture. More like how Matisse and artists before him would think about painting. But then art history that we studied basically decontextualized painting from the wall. Studying art history we just look at one image.

You rarely see someone like Rothko saying, Well, I want these images to be together. They should be installed in such and such ways. That is why I became interested in the relationship between the painting and where it’s installed. And I think as you break the frame a bit by painting on the couch or by painting on the wall, mixing it with painting or any other way, you immediately call into questions of politics and economy and anthropological rituals.

So to summarize it: It touches on the questions of alternative modes of relationality. It poses the question how can we relate differently? In the Melly exhibition, that was why we wanted to have one of the works outside of the room looking like a poster, and we wanted the clouds to move towards the window where it relates to the outside landscape. We wanted the couch to be a condensation of the entire boomgaardstraat and the whole neighborhood. So you have all these relationships in a metaphoric way.

You made a painting about the Dutch painter Rene Daniels as well. Is that also related to his use of space and the interested he had for psychoanalysis?

Absolutely. That painting was a homage to two of his paintings. One of them is called Aux. In it he shows Razi and Ibn Haytham (Alhazen), two Muslim opticians who introduced a theory of optics in the 12th century, and they are connecting an auxiliary cord to this European theory of perspective. It’s such a beautiful homage to history of optics and perspective.

Daniels used geometric lines of Islamic art in quite an ironic and funny way, turning it into an auxiliary cord one uses to plug into your amplifier. He’s connecting our Western theory of perspective to that theory of optics that the Islamic world introduced in the 12th century

In my homage I painted a few of my own drawings I chose from my ten years of drawing. I called it Rene Daniels Academy. So he has all these different styles of painting – a Japanese painting, a drawing of a model, a surrealist painting, calligraphy, writing and still life – which brought into a different perspective. And he has also painting of candle and candle is also very common theme in Persian painting. And I have also this.

In an interview with art magazine Mr Motley you mentioned that the Dutch are very much geared to it towards the Anglo-Saxon world and seem to have forgotten about their own past, also when it comes to participation in public discourse. You said wanted to step in, as it were. Was your show at Melly an attempt at participating in public discourse?

I was very satisfied with the experience at Melly. Although I was expecting more media attention considering all the newsworthy questions on the name change (from Witte de With to Melly, ed.), maybe there has been and I yet have to tune in. Now that the painstaking job of archiving is being carried out, other cultures are being recognised for their contribution to Dutch history. With all the contending political ideas, modes of painting and history of painting all merging in Melly, I expected there to be more of a dialogue. I think we are drawn to the Anglo-Saxon world because they do a great job, meaning that they have a specific history in shaping museology. They put things out there and say with confidence: this is the way.

Since you’re interested in politics or political discourse, I was wondering if you are working on something reflecting the current events in Iran?

I think becoming an artist itself is so political, even if you don’t necessarily show politics. I think 1001 nights is one of the greatest political positionings in the history of Iran. 1001 nights is an example of politics by artists in Persia. How to use beauty to introduce ethics.

Also, at some point you realise that the excess of catastrophes exceeds your capacity to capture screenshots of history. Therefore, you must produce something that is not journalistic because journalism on Iranian politics is gone by the wind every day. Some 70, 80 days have passed since the revolution. There are 2 to 3000 important points and letters and pieces that can be curated. As an artist, what can you do?

We need to produce works that transcend all this in order to create an analytic space to think and be political. I don’t produce political content. I produce the space within which political thinking should become possible, and I think that should be my role as an artist.

So, the politics is in the form and context?

I think my position was always to use aesthetics. Formalism and beauty and decor, uncertainty and to think of what will remain and keep things together.

So my Nastaliq paintings are just as political as Rene Daniels was. He decentralizes Europe in European art history, that’s as political as when you paint a Muslim Indian boy who is now under the fascist state of India. Also, I think Pasolini’s film 1001 night was dealing with fascism as much as his Salo was. Bonnard was purposefully distancing himself from avantgarde artists because he realized its machismo was feeding fascism. He opted for a more feminine and decorative approach instead.

All of these were political positions. It’s just that our art, our art history hasn’t touched on it as such, and our institutions haven’t managed to take a strong position on them. Maybe there are some institutions have, and some have not. So, I don’t think that as one artist I can do the Herculean job of changing the narrative for everyone.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel

Making a feature film on your own seems impossible in advance. Yet, this exactly what artist and filmmaker Bob Demper is trying to do. He exchanged the rigid film world for his own creative approach, in order to achieve the same result with intermediate steps. At Prospects, Demper shows such an intermediate step: Black Rock, Soft Storm. An installation in the form of a generic American office. It is the workplace of Donny, the main character in his forthcoming feature film.

Black Rock, Soft Storm

Demper has been working on 5000 Miles for over 4 years, a film that he partly shoots in the US and partly in his studio in The Hague. In recent years, the pandemic has forced him to revise his travel plans. Still, he was productive. The restrictions imposed gave him time and the opportunity to experiment.

“The movie is a long-running project from which smaller projects regularly emerge. Black Rock, Soft Storm is such a smaller project,” says Demper over the phone. This installation consists of the decor of the workplace of main character Donny, an anonymous office space behind a cold glass front. A scene from the movie can be seen on Donny’s PC, while a benign storm rages outside. On large LCD screens, which act as a window, many large, soft objects are pressed against the glass.

Mental composite drawings

The idea of considering set pieces as spatial installations came about gradually. Seen from the right angle, the imagined reality holds, but as soon as you step back, it’s gone. “From my interest in this fragility, which is very specific to cinema, paintings, sculptures and installations emerge that are both autonomous works and part of my films.”

For the design of his sets, Demper (The Hague, 1991) draws on his memory, or rather: his viewing experience. “Donny’s apartment is in New York. When designing that space, I included a window that faces an alleyway. When I was in New York, it turned out that alleys like these almost didn’t exist. They are missing in New York’s rigid grid, where there is no room for ‘useless alleyways’. The alleys stem from Hollywood’s vision of the city. Screenwriters in LA added them, because space is less scarce there. Partly because of this, they are part of our collective memory. Ask someone to imagine an apartment in New York, and everyone will have a mental approximation of what it looks like drawing on a wide variety of pop culture examples.” Mental composite drawings, Demper calls them.

A factory on wheels

Demper graduated as a film director from the HKU in 2014 and subsequently worked on Borgman and Schneider vs Bax, two more recent films by director Alex van Warmerdam. It was educational, but it made Demper realize that the film world was not for him. “When I decided to become a filmmaker, I thought that if you were far enough along in your career, you could find a way of filmmaking in which the making process, especially the shooting days, would leave a lot of room for adventure. The reality is that as that ‘factory on wheels’ gets bigger, it also becomes less and less agile. Van Warmerdam does have creative freedom, but like any other filmmaker, he is bound by the limitations of the medium. That was a disillusionment for me and that is why I understand that he also paints”

Demper therefore recognizes himself in the statement of Alfred Hitchcock, who once said that he liked coming up with a project, but did not find the filming itself particularly exciting. What Demper especially missed while shooting was a lack of experiment, it was the mere ‘execution’ of an idea conceived earlier, as is possible in other disciplines such as painting or sculpture. With film this is only possible if you take matters into your own hands.

Demper’s preference for a method dictated by the process also means that the budget is a fraction of a full-length feature film, which in turn means that he pretty much does everything himself, both in front of and behind the camera. For example, in 5000 Miles, the limited number of actors is accommodated by making them wear masks, allowing the same actor to play multiple roles. The cottage on the still-timbered Damper in the Nevada desert during a residency. “Before I would stay in the desert for two weeks, I did not know that the house was coming. That came to me there and then. That’s how I like to work, by building a set and spending some time there.”

Blackrock

Some degree of headstrongness is thus not foreign to Demper. A good example of this is his website, which is completely textless except for a few lines of a modest pop hit. Even contact information is missing. At the same time, the themes he addresses in Black Rock, Soft Storm stem from a great involvement with his immediate surroundings. For example, the main character Donny is at home dealing with a burnout, just like a number of people in Demper’s immediate environment.

His interest in Donny’s employer, an American asset manager, does not come out of the blue either. In addition to his art practice, Demper works for a company that records shareholders’ meetings, which piqued his interest in the world of finance and power structures.

The asset manager Donny works for is Blackrock, which manages about one-tenth of the total assets of the entire world. Such companies are dedicated to risk management. They operate by spreading investments, not only across different sectors, but also across the globe. For example, the company is controversial in the Netherlands because of the adverse effects their real estate portfolio has on the Amsterdam rental market.

To contain investment risks, the company has developed Aladdin, software that predicts market risks based on past events and personal information of millions of people. On this basis, the system shifts shareholders’ assets, resulting in more stable financial markets and therefore more certain returns forecasts. “In such a world, real change seems impossible, because an algorithm predicts and corrects every outlier,” says Demper. “Not only is it slowly eroding a way of living together, but above all I think it is an anxious continuation of a disenchanted world. A world in which there is less and less room for personal feelings, magic or anything that cannot be expressed in figures or manageable units.”

Bob Demper’s work can be seen during Art Rotterdam in the Mondriaan Fund’s Prospects exhibition. For the 11th time in a row, the Mondriaan Fund presents the work of 73 starting artists. In 2021, all artists received a financial contribution from the Mondriaan Fund to kickstart their careers.

Written by Wouter van den Eijkel

During Art Rotterdam, you will see the work of hundreds of artists from all over the world. In this series, we highlight a number of artists who will show remarkable work during the fair.

The versatile work of Toon Boeckmans is not easy to capture or classify. The Belgian artist makes installations, videos, paintings and drawings. Through his practice, he searches for the poetry in the mundane. He often uses found material for his works, or he creates visual references to familiar objects himself. From mikado sticks and old board games to red and white barrier tape, completely silver traffic signs and a blank tear-off calendar that even fails to mention the date. Boeckmans creates these objects from scratch or he transforms found objects using minimal, yet witty and sophisticated interventions. That way, familiar symbols acquire new meanings, functions, contexts and connotations, and the resulting works often have both humorous and dystopian undertones.

Yet the overtone in Boeckmans’ oeuvre is often playful. Because he uses or imitates such well-known objects, he invites recognition on the one hand, but on the other hand his unconventional compositions actively put you on the wrong track. In 2022, the artist presented a drum with 22 horses on it that seemed to originate from a chess game. A chessboard, a regulated universe that is characterised by laws and strict rules, only has four knights. Seeing 22 chess horses may therefore cause some confusion for the viewer, but in that chaotic situation there is also room for a new, more intuitive interpretation. Dark and light pieces are mixed, in a dynamic composition — as if they were on a dance floor and could start moving at any moment. Another connotation could be the carousel, which is also marked by the presence of wooden horses.

In many cases, Boeckmans’ works are not linguistic, in the sense that they rather refer to a universal, non-verbal form of communication. Sometimes, however, it is precisely the title of the work that evokes a smile, such as the cheerful yellow “Fort from Soft Butter” (2015) which, as the name suggests, consists of a composition of pieces of butter, that form a fortress that’s just two blocks of butter tall — unfunctional as a defense mechanism in more ways than one. But however intuitive and impulsive some works may seem at first glance, the ideas first arise on paper, after which they are carefully thought out and developed. The viewer is then invited to think of their own interpretations.

Boeckmans studied Mixed Media at Sint-Lucas Beeldende Kunst Gent. The program presents the artist on their website in a list of alumni who have managed to secure a place in the art world, as a success story for prospective students. Boeckmans’ work has previously been shown in the Concertgebouw in Bruges, twice in the Summer Salon in Kunsthal Ghent and Dauwens & Beernaert Gallery presented his work at Artissima in Turin, in Ballroom Project in Antwerp and during Art on Paper in Bozar in Brussels. His work is currently also on display in Gevaertsdreef 1 and Merode Ronse.

During Art Rotterdam, Toon Boeckmans will show his work in the booth of Dauwens & Beernaert Gallery in the New Art Section.

Written by Flor Linckens

During Art Rotterdam, you will see the work of hundreds of artists from all over the world. In this series, we highlight a number of artists who will show remarkable work during the fair.

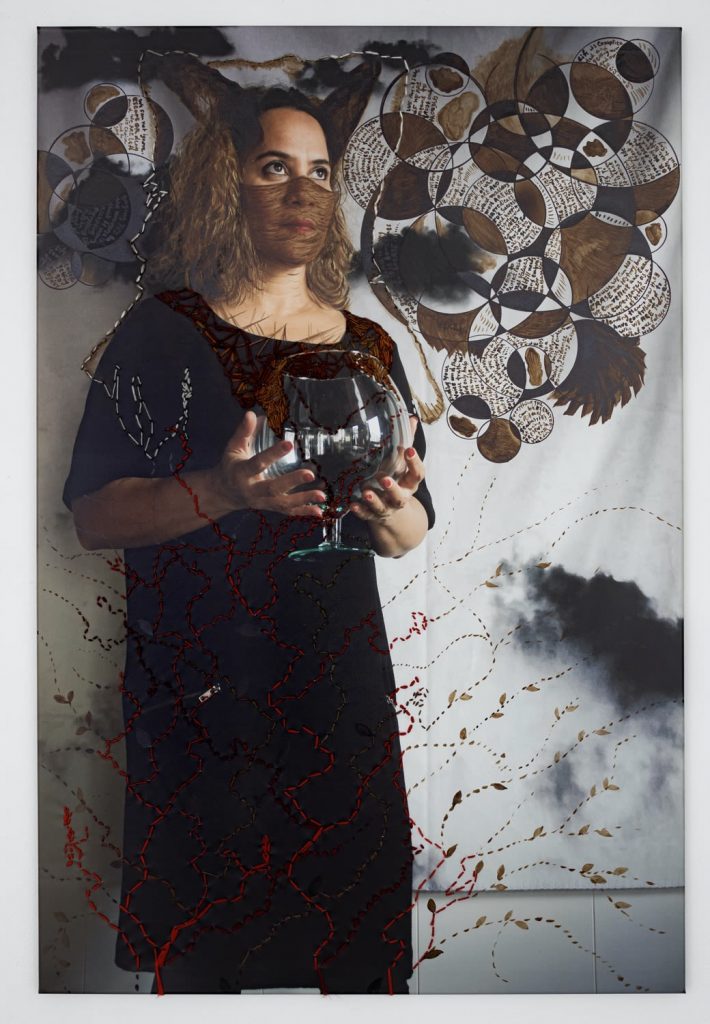

Monali Meher works in a multitude of disciplines: from video, installation and performance to photography and textiles. But it is performance art that occupies the most prominent place in her practice. The body plays a central role in this, alongside recurring themes such as time, a sense of belonging, migration, cultural cross-pollination, a hybrid and diaspora identity, gender, intimacy, decay, the climate, transformation and the reshaping of objects and memories — often in a social or political context. In fact, time, and the physical and spatial dimension of time, is such an essential part of her practice that it almost counts as a medium in itself. She compresses or stretches the concept of time. The artist is also interested in oppositions such as sadness and happiness, continuity and transience, birth and death.

Meher’s practice is a continuous quest in which she mirrors her own experiences through the media she chooses. Sometimes certain objects play a role in this, often transitory or natural in nature. When the online platform ITSLIQUID asked her about her personal interpretation of art in 2014, Meher stated: “Art is the language, the body, an expression, emotion, sound, pain, struggle, growth, change, statement, something which stays with you in your memory and/or changes it’s form over a period of time.”

In recent years, Meher has performed a number of compelling performances. She used her body to simulate the almost imperceptibly slow change of nature in the performance “Gilded” (2022), amidst a staged natural landscape. She made stone soup in Kunsthal Gent and in 2011 she organised a ‘Silent Walk’ on the Museumplein in Amsterdam as part of International Migrants Day, specifically in the context of the worldwide art campaigns of Tania Bruguera. In 2021, she presented a performance in De Kerk in Arnhem. For this she painted 700 kilos of potatoes in black paint with words with a negative connotation. In different languages you could read words like “anger”, “violence”, “hass” (hate), “guerre” (war) and more. Visitors were invited to peel the potatoes to remove their (emotionally) toxic skin. The potatoes were then donated to various homeless institutions and the sustainable local restaurant De Stadskeuken. When the performance ended early due to a lockdown, Meher continued the project on her own. Later in 2021, Meher presented a performance in a snowy valley in Norway. In “Arctic Action VI” she wrapped yellow, green and blue transparent fabric over an old rusty oven, which had previously been used for burning garbage. Meher: “I started wrapping objects in 2005, transforming, giving them new skin with the aim to make emotions emerge from them.” The Arctic Action project, that the performance was a part of, draws attention to the fragility of the planet and the relationship between human beings and nature.

Meher graduated from the Sir J. J. School of Arts in Mumbai in 1998. In the same year, she travels to Vienna, where she is invited for a UNESCO-Aschberg residency. In 2000 she started a residency program at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam and remained in the Netherlands after that. In 2004 she briefly traveled back to India, where she participated in the Khoj residency project in New Delhi for two months. She currently lives and works in Ghent.

In the Belgian magazine rekto:verso, Meher wrote that it can frustrate her when people always center her Indian background, even in the interpretation of her work — and with that her “otherness”, an expression of “othering” in the terminology of Edward Said. Meher mentioned that she initially adapted to the Netherlands by applying a neutral palette, but that none other than Marina Abramović advised her to embrace her background in her artistic practice.

In addition to performances, Meher also creates work on paper. Meher: “Drawings for me are like autobiographical diagrams. My use of natural and ephemeral ingredients results in a process of perishing and transitory moment of the time. I transform the nature of manner in which materials react, what shape or smell they produce, what impact they make on my viewers and how the space around my art and audience gets transformed.” Meher enriches these works with food colouring, inks, pigments, face paint and sandalwood oil, which are then used as a means to soothe physical and mental pain. In combination with the images, this creates a number of almost ritual acts.

Meher has shown her work at Tate Modern, the National Gallery of Modern Art in India, the Van Gogh Museum, the MAXXI museum in Rome, the Sinop Biennale Turkey, DaDao Beijing, the Venice Experimental Cinema and Performance Art Festival and the Arezzo Biennale, where she won the Golden Chimera Award for innovation and originality. In the Netherlands, her work is included in the collections of the Centraal Museum and the AkzoNobel Art Foundation, among others.

During Art Rotterdam, Monali Meher will present her work in the booth of Lumen Travo Gallery in the main section.

Written by Flor Linckens

Zoro Feigl (NL 1983) has his office in Amsterdam, but works in the Belgian Kempen region where he has a large outdoor studio. Space is essential for Feigl, as his installations are usually large and noisy. Feigl has always had a fascination for ‘how things are put together’. Only later did he realize that this had to do with art. Initially, he studied design in Utrecht, and enjoyed himself there, but got stuck because he didn’t stick to the instructions of his teachers. He ended up at the Rietveld Academy, where he graduated in 2007. In 2011, he followed a further education at the HISK in Ghent. His work has already been shown at Art Rotterdam, where he won the prize for the best presentation at Intersections in 2015.

On Saturday 14 May, Feigl’s solo exhibition Zonvonkengesproei will open in the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, a stone’s throw from the Van Nelle Factory. The museum opens its doors after a thorough renovation that lasted two years. Ellis Kat is involved in Zonvonkengesproei as a curator and talks about the effect the newly renovated museum had on Feigl’s work, his method and the ideas behind his work.

You have built up the exhibition over the past few days. Is that different with Zoro’s machines than with an exhibition with two-dimensional works?

Past days?! Past weeks, you mean. Due to the size and complexity of the installations, a large team spent weeks building it up. In fact, work on this exhibition started about three years ago. Initially, Zoro’s solo exhibition was planned just before the renovation. He was given a license to use the spaces as he wished, as the museum would be renovated afterwards anyway. Everything was cut and dried, the works were ready for transport and then the lockdown followed. It was decided to renovate first and postpone the exhibition.

A big difference in curating this exhibition compared to an exhibition with two-dimensional works is that paintings are usually completed in the studio, transported to the museum where they are unpacked and hung. Now every installation was actually made in the museum itself. Zoro’s studio in Belgium is large, but an eighteen meter long installation such as Getij cannot be completely built there. So the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam actually functioned as Zoro’s studio for weeks. Only there and then did it become clear how it all came together.

In some cases Zoro made a smaller version of a work in his studio, such as the work Fosfenen, which consists of countless moving mirrors that reflect in space. He first showed me that version in his studio amid the clutter and in the semi-darkness. In the museum it really comes into its own and I saw the magic of the end result.

Is curating an exhibition like this different from a ‘normal’ exhibition?

I’m afraid a normal exhibition doesn’t really exist. Zonvonkengesproei is a special exhibition to curate. More than ever I have learned that the place where an exhibition takes place plays a fundamental role. At first we were in the midst of the renovation, during which he was given carte blanche to demolish the museum. Now, Zoro was obliged to act neatly; he not only ensures that the new building is not damaged, but with his art he knows how to unlock the new elements in the halls for the visitor. It has become a completely different exhibition. Due to these circumstances, Zoro had to work very carefully and he has shaken off the bad boy image. When you think of his installations, you envision robust, twisting, spinning machines. Now I have seen how ingenious, concentrated and skilful Zoro works. In retrospect, the pandemic is a gift to the renovated museum and Zoro’s artistic development: they pull each other up.

The exhibition comprises six rooms. Do those rooms provide a survey of Zoro’s work or are they six recent or new works?

It is almost all new work. Only Zwermen, an installation that the museum acquired in 2020, has been on display before. The works in Zonvonkengesproei mark a new step in Feigl’s oeuvre. He has grown up. It remains kinetic work and it does make noise, but it was made with a lot of attention, so that the visitor also dares to give that attention to the works. He has managed to get to the core of his artistic practice.

The exhibition is called Zonvonkengesproei. What does that mean and why exactly does that term cover the charge?

That is a neologism, a non-existent word that comes from Herman Gorter’s 1889 poem Mei. In the poem the girl Mei meets the love of her life, Balder. She is in ecstasy and directly projects her feelings onto the young god. It’s such an overwhelming feeling that she can’t quite put it into words and that’s why she uses this word. Zoro’s work evokes a similar overwhelming feeling. It’s so all-encompassing that it’s hard to describe.

What is the core of Zoro’s artistic practice you were talking about?

In his work Zoro tries to incorporate natural phenomena and everyday things in installations. Think of the behaviour of a flock of starlings, ripples in the sand in the surf or glowworms on your retina, which you see when you close your eyes for a long time. They are things that happen, but which we cannot influence. No human can control the way a flock of starlings moves in the sky, no matter how much we think we have power over nature. Zoro does try to seize these elusive situations and make them accessible in his work. Suddenly he takes control. Just for a moment, because when he turns on his installations, all the balls – the starlings, or the mirrors – the glowworms – all go in a direction that he could never have predicted himself. The work itself has come alive again. If you have seen his installations, hopefully when you exit the exhibition you will notice everyday things that you previously passed by.

How does Zoro work? Does he start from an idea, a vision, or rather from material that he finds interesting?

Zoro has no set method. Some works, such as Floating Floor, are created by association. One evening, Zoro took the bag from a 5-litre carton of Aldi wine, squeezed it and watched the wine flow to other parts of the bag. A kind of waterbed effect. What if we have floors like this, he wondered. In Schiedam you can now walk on a parquet floor that is constantly sagging. Another example is the installation Lianen, which is displayed in the attic of the museum. This installation consists of four metal ribbons that are driven by motors and that wind continuously. Together they form a choreography. Like many of his installations, this one takes on a more human character the longer you look at it. The idea for Lianen was a package that was closed with tie-wraps, they flew away when he cut them open. This uncontrollable effect intrigued him and he tries to capture it in a work. However, the reason for a work can also be much more pragmatic. It also happens that a material has been wandering around in his studio for a long time, he keeps tripping over it and decides to use the material, so that it is finally cleaned up. Not having a set method ensures that Zoro is always open to play and accidental discoveries.

Zoro often uses classical mechanics in his work. Motorcycles in all shapes and sizes. Why does he use this rather dated technology?

Why does a painter use paint? I disagree that he uses outdated technology. Now that I had a look behind the scenes, I see how much modern technology is involved. An installation such as Getij consists of PCs at the back that control programmed choreographies of the bands. It is a combination of raw materials and modern techniques. The assumption that he only gets things from scrap to use in his work is patently incorrect. At times he spends weeks looking for a specific part of his installation to finish it exactly the way he envisioned. He received this time from the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, so that he has transcended his bad boy image.

In articles about Zoro’s work you often read something like: if you have ever seen a work by Zoro, you will not soon forget it. Can you explain why his works leave such a strong impression?

That’s Zonvonkengesproei; you can’t quite put it into words. Let me not say too much about it: just come to the exhibition, then you can experience it for yourself.

Abysses by Zoro Feigl can be seen at Art Rotterdam in the booth of Gallery Fred&Ferry.

The exhibition Zonvonkengesproei by Zoro Feigl can be seen from 14 May through 11 September in Stedelijk Museum Schiedam.